These two pieces, published today in the New York Times, go hand in hand--one, about the rise in the rates of suicide and depression in New Orleans, and the other about a total lack of plan.

First:

June 21, 2006

A Legacy of the Storm: Depression and Suicide

By SUSAN SAULNY

NEW ORLEANS, June 20 — Sgt. Ben Glaudi, the commander of the Police Department's Mobile Crisis Unit here, spends much of each workday on this city's flood-ravaged streets trying to persuade people not to kill themselves.

Last Tuesday in the French Quarter, Sergeant Glaudi's small staff was challenged by a man who strode straight into the roaring currents of the Mississippi River, hoping to drown. As the water threatened to suck him under, the man used the last of his strength to fight the rescuers, refusing to be saved.

"He said he'd lost everything and didn't want to live anymore," Sergeant Glaudi said.

The man was counseled by the crisis unit after being pulled from the river against his will. Others have not been so lucky.

"These things come at me fast and furious," Sergeant Glaudi said. "People are just not able to handle the situation here."

New Orleans is experiencing what appears to be a near epidemic of depression and post-traumatic stress disorders, one that mental health experts say is of an intensity rarely seen in this country. It is contributing to a suicide rate that state and local officials describe as close to triple what it was before Hurricane Katrina struck and the levees broke 10 months ago.

Compounding the challenge, the local mental health system has suffered a near total collapse, heaping a great deal of the work to be done with emotionally disturbed residents onto the Police Department and people like Sergeant Glaudi, who has sharp crisis management skills but no medical background. He says his unit handles 150 to 180 such distress calls a month.

Dr. Jeffrey Rouse, the deputy New Orleans coroner dealing with psychiatric cases, said the suicide rate in the city was less than nine a year per 100,000 residents before the storm and increased to an annualized rate of more than 26 per 100,000 in the four months afterward, to the end of 2005.

While there have been 12 deaths officially classified as suicides so far this year,

Dr. Rouse and Dr. Kathleen Crapanzano, director of the Louisiana Office of Mental Health, said the real number was almost certainly far higher, with many self-inflicted deaths remaining officially unclassified or wrongly described as accidents.

Charles G. Curie, the administrator of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, said the scope of the disaster that the hurricane inflicted had been "unprecedented," and added, "We've had great concerns about the level of substance abuse and mental health needs being at levels we had not seen before."

This is a city where thousands of people are living amid ruins that stretch for miles on end, where the vibrancy of life can be found only along the slivers of land next to the Mississippi. Garbage is piled up, the crime rate has soared, and as of Tuesday the National Guard and the state police were back in the city, patrolling streets that the Police Department has admitted it cannot handle on its own. The reminders of death are everywhere, and the emotional toll is now becoming clear.

Gina Barbe rode out the storm at her mother's house near Lake Pontchartrain, and says she has been crying almost every day since.

"I thought I could weather the storm, and I did — it's the aftermath that's killing me," said Ms. Barbe, who worked in tourism sales before the disaster. "When I'm driving through the city, I have to pull to the side of the street and sob. I can't drive around this city without crying."

Many people who are not at serious risk of suicide are nonetheless seeing their lives eroded by low-grade but persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness and stress-related illnesses, doctors and researchers say. All this goes beyond the effects of 9/11 and the Oklahoma City bombing, Mr. Curie said. Beyond those of Hurricanes Andrew, Hugo and Ivan.

"We've been engaged much longer and with much more intensity in this disaster than in previous disasters," he said.

At the end of each day, Sergeant Glaudi returns to his own wrecked neighborhood and sleeps in a government-issued trailer outside what used to be home.

"You ride around and all you see is debris, debris, debris," he said.

And that is a major part of the problem, experts agree: the people of New Orleans are traumatized again every time they look around.

"This is a trauma that didn't last 24 hours, then go away," said Dr. Crapanzano, the Louisiana mental health official. "It goes on and on."

"If I could do anything," said Dr. Howard J. Osofsky, the chairman of the psychiatry department at Louisiana State University, "it would be to have a quicker pace of recovery for the community at large. The mental health needs are related to this."

The state estimates that the city has lost more than half its psychiatrists, social workers, psychologists and other mental health workers, many of whom relocated after the storm. And according to the Louisiana Hospital Association, there are little more than 60 hospital beds for psychiatric patients in the seven hospitals that remain open here.

Because of a lack of mental heath clinics and related services, severely disturbed patients end up in hospital emergency rooms, where they often languish. Many poorer patients were dependent on a large public institution, Charity Hospital, but it has been closed since the storm despite the protests of many medical professionals who say the building is in good condition. Big Charity, as the locals called it, had room for 100 psychiatric patients and could have used more capacity.

"When you don't have a place to send that wandering schizophrenic directing traffic, guess what? Law enforcement is going to wind up taking care of that," said Dr. Rouse, the deputy coroner. "When the Police Department is forced to do the job of the mental health system, it's a lose-lose situation for everyone."

"When the family comes to see me at the coroner's office," he added, "it's a defeat. The state has a moral obligation to reinstitute this care."

Sergeant Glaudi and others said some people struggling with emotional issues had no prior history of mental illness or depression.

The symptoms cut across economic and racial lines; life in New Orleans is difficult and inconvenient for everyone.

Susan Howell, a political scientist at the University of New Orleans, conducted a recent study with researchers from Louisiana State to see how people were coping with everyday life in the city and neighboring Jefferson Parish. Ms. Howell managed a similar survey in 2003.

"The symptoms of depression have, at minimum, doubled since Katrina," she said. "These are classic post-trauma symptoms. People can't sleep, they're irritable, feeling that everything's an effort and sad."

The new survey was conducted in March and April, and canvassed 470 respondents who were living in houses or apartments. Since they were not living in government-issued trailers, it is likely that they were among the more fortunate.

Jennifer Lindsley, a gallery owner, also feels the sting of missing her friends.

"When you can't get ahold of people you used to know, it leaves you feeling kind of empty," Ms. Lindsley said. "When you try to explain it to people in other cities, they say: 'The whole world is over it, so you've got to get over it. Sorry that happened, but too bad. Move on.' "

Some people have decided to leave solely because of the mood of the city.

"I'm really aware of the air of mild depression that pervades this entire area," said Gayle Falgoust, a retired teacher. "I'm leaving after this month. I worry about living with this level of depression all the time. I worry that it might affect my health. I know the move will improve my mood."

And now, one of the causes:

June 21, 2006

EDITORIAL

The New Orleans Muddle

It has been almost 10 months since Hurricane Katrina battered the Gulf Coast, and there is still no redevelopment plan for New Orleans. Congress has passed the emergency relief bill, and President Bush has signed it into law. Billions of dollars are headed the city's way. Leaders in New Orleans and in the state capital of Baton Rouge will have only one chance to get it right. There are no more excuses for local officials, no more pointing toward Washington. It is time for southeastern Louisiana to rebuild itself.

Yet Adam Nossiter reported this week in The Times that it will be six months before a "master planning document" answers the questions foremost in the minds of residents, like which neighborhoods will return, where rebuilding will be encouraged and where returning residents will have to make do without city services. That is totally unacceptable.

In large swaths of the city, houses still sit empty, block after block. In many places, trash and flood-ruined automobiles have yet to be cleared away. These wastelands provide hideouts for criminals, the perfect breeding ground for the kind of violence that erupted over the weekend when five teenagers were shot and killed.

If the city's open wounds are left to fester, it will begin to rot from the inside.

The city's police department is close to its prehurricane size, protecting a population that is less than half of what it was before the storm. Yet Mayor Ray Nagin has now felt compelled to request — and the governor has granted — a National Guard force to help keep the peace. This does not bolster our confidence that the city will be able to govern itself.

New Orleans has its own way of doing things and says it doesn't want to be told by outsiders in what size and shape it should be reborn. That is fair enough, but only if local officials are living up to their responsibilities. Right now, the people of the city are being held hostage to whims and foot-dragging, their lives on hold as they wait for their leaders to make decisions — decisions that should have been made months ago.

If there is one individual who needs to step up more than any other, it is Mayor Nagin. His city needs a leader more than a politician in this difficult time. Now that Mr. Nagin has been re-elected, it is time to start spending the political capital his victory earned him. His legacy will not rest on how many people like him, but on the effectiveness of the reconstruction and the safety and well-being of residents in the years to come.

New Orleans needs its mayor to speak difficult truths — like telling the residents of a vulnerable block that they will have to rebuild on safer ground. Right now, people don't know if or where to build their new walls. They deserve answers. They have waited long enough.

********

My own brand of depression has come in the form of intense spells of rage that are not warranted by the situations that bring them about. Yesterday I had a bad one, and I spent most of the dinner hour crying into my Indonesian fried rice, wanting badly to be comforted by my husband, who had just been the focus of my rage. Who could blame him for eating his own food, ignoring my grief, and then leaving the room to organize his office? (He seems to focus his own anxieties into spells of organization and miscellaneous projects.)

Because Simon lost his job after the storm, we have been living on extremely limited funds. Lucky for us, our landlord has not raised the rent, and so we made the decision last week to purchase a second car (mine was totalled by a drunk driver as it sat parked in front of our house... another long and depressing tale). We applied for financing through the UNO federal credit union and were told that if we purchased a car five years young or less (our 2001 Civic made the cut), we would get 5.99% financing. All seemed well.

But yesterday, when Simon returned from taking the car's purchase order to the bank, he told me that in fact the rate was 12.99%. We needed to purchase a 2002 or younger, he said. We would need to contact the car dealer to try to get a better rate.

I was angry. Really angry. But I contained my anger and argued (quite logically, I might add) that the credit union KNEW we were applying for a loan for a 2001 Civic (this is true,) and now that we had f-ing agreed to BUY the car they were telling us no?!

I called customer service for my credit card. They are offering 3.99% for the life of the balance on major purchases. Sounds great, but it means that the initial balance--at 15.99%--sits on the card longer and longer (you pay off the balance at the lowest rate first, of course.) So really we are simply lengthening the term of a 15.99% rate loan (sorry if I am boring you). No way out yet.

But it was the next news that got me. After taking a shower, Simon announced calmly that his account--the one whose plans were meant to be deposited in our new account--was overdrawn, which means, well, that he's running on empty. We recently opened a joint account and had agreed to spend our money responsibly. I think we've both been making an effort, too. But I was so angry that he had overdrawn his account that I just HAD to say some mean-spirited crap about the irresponsibility of it. (I mean, Christ, does ANYONE really need to be told this? No! So why did I have to say anything?)

Well, Simon reacted as anyone would--defensively. Did I want to talk blame, he asked (referring to my small mountain of debt--which I have been gradually chipping away at and NOT adding to, thank you very much!) I didn't.

No--but what I did want to do was scream at the top of my bloody lungs at him. I'm talking crazy, gutteral scream. Not just a yell; an all-out, blood-curdling SCREAM. It feels good when it happens, really. A kind of release--like a tiny hole in a big old dam and so that water comes f-ing SHOOTING out. A release like when you're angry and you scream into a pillow. Only I thought, screw the pillow, and subbed my husband.

I don't even remember what I said--or screamed--but I do remember how I felt: I wanted to hurl my plate of hot food at him. I wanted to break shit. I wanted to physically hurt something or someone. Preferably something that would make a noise as it went. Maybe his skull.

This is bad. This is the kind of behavior one gets asked about at one's shrink. ("Have you felt like hurting others or yourself?") For the first time I can recall, I would answer, "F--k YES!"

What is this rage all about?

It is the buildup of anxiety. It is trying to be and feel okay in an environment that is entirely broken. It is dealing with a very VERY uncertain future--and being newly married and afraid. It is resenting Simon for not having a job--and the city for not being able to provide a good one. It is stress and worry and now it is driving a car that we will pay for, yes, but which will end up costing us at least two grand more than we budgeted. It is knowing that no matter the outcome, it will, for a very long time, NOT be okay.

As I cried over dinner, I told Simon that I was sorry for my misdirected anger, but that I couldn't seem to channel mine like he does. Cleaning and organizing don't do it for me. What does it for me is comfort. It's being told we will be okay. It's BELIEVING we will be okay because there is an OKAY in sight.

But right now, here, in New Orleans, there isn't an okay in sight. There is no okay on the horizon, either. There is endurance and these occasional spells of rage, punctuated, occasionally, by hopeful (or is it really hopeless?) celebration of An End--The End (and we hope, a happy one)--that we cannot see.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

We are a broken set of Christmas lights here. The old kind: one light's going causes the rest of the string to go dark. Such was the case last night, when Simon and I were turning in for the night. We'd settled in with our reading--I with a short story collection and Simon with a thinking-man's magazine--when the power went out.

Had I known the outages would be so regular (there has yet to be a month since we've returned that we've nto had at least one) and so frequent (particularly when the wind blows or a single rain "drops,") I might have kept score, tried to make a game of it. One needs to do that now. And once upon a time--months and months ago--the outages had their charm. How rustic! How spontaneous! See how we can do without TV! See how much we are willing to put up with for our beloved New Orleans! Cheers, cheers, cheers! We went out for a walk in the dark back then, admiring the hue of FEMA tarps in the moonlight. Or we stayed inside, lit dozens of candles, and played romantic.

But it happens again and again, and the fragility of our power grid does, indeed, make life in New Orleans seem very third-world. Very un-charming. Anger-inspiring. And yet, never the least bit surprising. Even the outages that are apropos of nothing are old news to us. (Usually it is rain or even the lightest of winds that causes the power to go.) And yet.

And yet last night I just wasn't HAVING it. The night was perfectly still. It was hot and the air thick, thick, thick, but there wasn't any heat lightning or other evident reason for power failure. So I called 1-800-9-OUTAGE (as I do) to find out the estimated time of repair (usually the patient but frazzled customer service rep at Entergy will give you a ballpark hour that is at least somwhat accurate). I sat on hold.

We are angry at Entergy here. Not only do they have a monopoly on our power in the city, but they also play the Katrina-card and blame everything on that f-ing storm. The hardier ones among us urge patience and understanding, but when one pays their bills, damnit! When one is living in America, for chrissakes! Well, we want a single drop of rain to be allowed to fall without our losing electricity!

It was a single drop of rain that appeared to cause our last outage two weeks ago. My dear friend, Jackie, who is indeed, hardy as hell, went to the French Quarter and had a T-shirt made that said "Got Electricity?" We in the Marigny-Bywater all laughed. And yet.

I was on hold. For a long time. The recording mocked me, saying, "Entergy cares about your high heat bills. Winter is here, and Entergy has a few simple steps that can make a difference in your bill." WINTER is here!?

Finally, after, I don't know, a dozen runs-through of this recording, I spoke to someone. They had only begun to receive calls fifteen minutes ago, she said. They were working on figuring out the problem, she said. Would I like a wake-up call? I would, dammit, yes. (I scheduled one for Simon, whose alarm clock plugs in.) If I can't have electricity, then I am entitled to concierge service as consolation, thank you very much.

The power stayed out until 4:30, and I couldn't sleep. It was HOT. Our house is always hottest at night (and coldest, too, when it does get cold), and I tried not to move as I lay on top of the covers, nude. At 2:00 I went into the kitchen and made an ice pack wrapped in a towel. Put it under my neck. I finally slept.

When the power came back on, our neighbors' ridiculous alarm system squealed, the ACs all churned back to life, and the lights we'd not yet turned off all came on. Simon and I stumbled around switching them off, cranking up the window units to high. Somehow used to our little power-restoration dance by now, we didn't even speak. Just dealt and went back to bed.

Six-thirty was mean this morning, but worse was the news that the power outage was the result of a fire in the neighborhood. I told Simon about it when he came home this afternoon from his occasional construction work. I was trying to nap, and was cranky because here he'd woken me up. "Well, at least there was a good reason for the outage," he said.

"Whatever," I replied (as usual, inconsolable these days). "What, are we like an old string of fucking Christmas lights--where one goes out and all the rest do, too? What the hell?!"

Simon smiled. "We are," he said. "We're just a broken string of Christmas lights." Then he rubbed my feet and I let myself smile, too.

Monday, June 19, 2006

Before I post Adam Nossiter's recent NYTimes article, I should confess that I have, in the past, found Nossiter to be a complete alarmist. In the days immediately following the storm, he was one of the irresponsible journalists who fell into a dangerous pattern of generalization and stereotype. Not what we needed.

Still, this time he's got us right:

June 18, 2006

In New Orleans, Money Is Ready but a Plan Isn't

By ADAM NOSSITER

NEW ORLEANS, June 17 — Billions of federal dollars are about to start flowing into this city after President Bush on Thursday signed the emergency relief bill the region has long awaited. But, with the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina approaching, local officials have yet to come up with a redevelopment plan showing what kind of city will emerge from the storm's ruins.

No neighborhoods have been ruled out for rebuilding, no matter how damaged or dangerous. No decisions have been made on what kind of housing, if any, will replace the mold-ridden empty hulks that stretch endlessly in many areas. No one really knows exactly how the $10.4 billion in federal housing aid will be spent, and guidance for residents in vulnerable areas has been minimal.

A month into his second term, Mayor C. Ray Nagin has said little about his vision for a profoundly different city. In an interview on Friday, he said it would be six months before a "master planning document" was issued to address questions like which areas should be rebuilt, although he suggested that thousands of residents were making that decision on their own.

Caution should be the watchword, Mr. Nagin said, months after the apparent demise of a planning committee he set up. "New Orleans is a very historic city," he said. "We can't come out and just do something quickly."

But a close collaborator of Mr. Nagin acknowledged that the process has lagged. "Let's just admit something straight out: we're late," said David Voelker, a board member of the Louisiana Recovery Authority.

Mr. Voelker, who is in charge of the state authority's efforts to coordinate with neighborhood planning, sounded uncertain even about the nature of the master plan.

"I don't know what this master plan is going to say, because I'm not a master planner," Mr. Voelker said.

The lack of a redevelopment plan and the state of the city's ruined neighborhoods have some worried that the city government has lapsed into the pattern of inactivity for which Mr. Nagin was criticized before last month's election.

"The city desperately needs leadership on planning and housing issues," an editorial in The Times-Picayune said last week. "Without strong guidance from City Hall, crucial decisions about the future of New Orleans will be made by default. Or they won't be made at all."

In occasional public appearances, the mayor has voiced characteristic optimism. "Today is another great day in the city of New Orleans," he said Wednesday after the A.F.L.-C.I.O. announced a $700 million housing and economic development grant. He called the grant "an incredible tipping point," but offered no specifics about which neighborhoods he was committed to rebuilding.

The mayor's flurry of appearances before the election has been sharply curtailed. Streets remain abandoned, sometimes for miles, and blocks are carpeted with trash.

"We do need to have a clear vision from the mayor," said Oliver Thomas, the president of the New Orleans City Council. "Tell us what you're for, or not for. We don't know exactly what neighborhoods he's committed to, kind of committed to, and not committed to."

Mr. Thomas added, "We don't know specifically what the roles of the neighborhoods are going to be in the new New Orleans. Can people build anywhere? Can they live anywhere? Are they going to be funded? We don't know that."

In the absence of a redevelopment vision from the city, residents are pushing ahead on their own, a process likely to be accelerated late this summer when washed-out homeowners begin receiving checks from the federal housing money appropriated by Congress. Whether homeowners who are rebuilding in ruined areas will remain isolated pioneers or will receive city services is still unclear.

A few badly damaged neighborhoods have undertaken their own planning efforts. "The initiatives for planning and rebuilding are coming from the neighborhoods themselves," said Pam Dashiell, a member of the Holy Cross Neighborhood Association, in the city's Ninth Ward.

The Broadmoor district, with a mix of incomes and races, has plans for converting abandoned dwellings to community use and wants to provide housing incentives for police officers and firefighters.

But few neighborhoods are as far along, and none of the efforts are being centrally coordinated.

During the recent election campaign, Mr. Nagin and most of his rivals carefully avoided pronouncements on the fate of specific neighborhoods, tiptoeing through a volatile issue that had many residents on edge. But now, critics say, the mayor does not have politics to use as an excuse.

"The election is over, and it's time for governing," said State Representative Karen Carter, Democrat of New Orleans. "He's the mayor, and he has to show that level of leadership and engagement."

Within a week of his re-election on May 20, Mr. Nagin announced that two ex-rivals from the campaign — both lawyers, one a Republican and the other a Democrat — would be aiding him in urgent planning for the city's future. In 100 days, there would be a plan, it was announced.

Since then nothing has been heard from either lawyer. One was traveling outside the country this week, and the other did not return calls.

In the interview on Friday, Mr. Nagin indicated that the entire city west of the Industrial Canal would be rebuilt, a more optimistic projection than some urban planners had given.

As for areas east of the canal, the mayor said that the prosperous New Orleans East area would probably come back and that the flattened homes of the Lower Ninth Ward would probably be replaced by what he called "multilevel living facilities," presumably apartment buildings.

Success, he said, is more likely to be defined by what residents do than what the editorial board of The Times-Picayune says. The city's current population of 220,000 is ahead of most projections, he said, and was made possible by his administration's willingness to provide building permits to almost all who asked, in any neighborhood.

"I think that most citizens can make intelligent decisions," Mr. Nagin said. "This city will be rebuilt. Most areas will come back. There are people who are rebuilding."

Mr. Nagin appears to be counting on a strategy that involves large-scale economic development projects, like one unveiled two weeks ago that called for demolishing a decrepit downtown shopping center and the city's frayed municipal complex and replacing them with a National Jazz Center set in a 20-acre park. Such development promises, largely unfulfilled, were a feature of Mr. Nagin's first term in office.

As for the planning body created after the hurricane, the Bring New Orleans Back Commission, little has been heard of it for months. The commission's tough plan, unveiled in January and now apparently dead, called for a four-month building moratorium in the hardest-hit neighborhoods while they proved their "viability." Ultimately a new public agency would have been empowered to seize land in areas that failed the challenge, and the city's footprint was to shrink.

Mr. Nagin, in the face of a public outcry, almost immediately rejected the plan.

Ray Manning, a local architect who played a key role in early planning efforts after the storm and who was a co-chairman of the mayor's neighborhood planning committee, said this week that he had withdrawn from the process.

"I said I would not speak about this issue any longer," he said.

At a conference at Tulane University this month, Mr. Manning had harsh criticism for the lack of guidance from City Hall.

For his part, the mayor in a brief appearance before reporters this week said of the neighborhood planning process, "That's just about completed."

Naming Mr. Thomas, the City Council president, as a collaborator, Mr. Nagin said, "There's a structure we'll be announcing in the next day or so, and we'll move that forward." But Mr. Thomas responded: "I don't know what the structure is. We've talked about some possibilities, but nothing definitively."

Now, 10 weeks before the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, some residents are losing patience.

"We are entitled to hear something now," said LaToya Cantrell, head of the Broadmoor Improvement Association. "We've been waiting. It's nine months out. We need to know what's going on. We need to know what the process is. The center of my community has yet to return, and this is nine months out. This is ridiculous. This is frustrating."

Interestingly, we here have become complacent, as one might expect. I remember feeling really, really ANGRY about the lack of a plan months ago. Now, I feel fatalistic, as if we all knew this was coming and should have expected it. You on the outside may wonder why we don't DEMAND change, or why we don't change things ourselves. But when we witness NOTHING CHANGING, we feel defeated, not motivated. Plus, our mayor is a WORTHLESS TURD who has done NOTHING in the interest of his own comfort. One of the strongest arguments for his ousting was that he simply NEEDS A BREAK. He feels as defeated as we do! How can this man make it happen for us!?

It's like my brother said. What we really need is a BENEVOLENT DICTATOR WITH REALLY GREAT IDEAS. Help!

Still, this time he's got us right:

June 18, 2006

In New Orleans, Money Is Ready but a Plan Isn't

By ADAM NOSSITER

NEW ORLEANS, June 17 — Billions of federal dollars are about to start flowing into this city after President Bush on Thursday signed the emergency relief bill the region has long awaited. But, with the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina approaching, local officials have yet to come up with a redevelopment plan showing what kind of city will emerge from the storm's ruins.

No neighborhoods have been ruled out for rebuilding, no matter how damaged or dangerous. No decisions have been made on what kind of housing, if any, will replace the mold-ridden empty hulks that stretch endlessly in many areas. No one really knows exactly how the $10.4 billion in federal housing aid will be spent, and guidance for residents in vulnerable areas has been minimal.

A month into his second term, Mayor C. Ray Nagin has said little about his vision for a profoundly different city. In an interview on Friday, he said it would be six months before a "master planning document" was issued to address questions like which areas should be rebuilt, although he suggested that thousands of residents were making that decision on their own.

Caution should be the watchword, Mr. Nagin said, months after the apparent demise of a planning committee he set up. "New Orleans is a very historic city," he said. "We can't come out and just do something quickly."

But a close collaborator of Mr. Nagin acknowledged that the process has lagged. "Let's just admit something straight out: we're late," said David Voelker, a board member of the Louisiana Recovery Authority.

Mr. Voelker, who is in charge of the state authority's efforts to coordinate with neighborhood planning, sounded uncertain even about the nature of the master plan.

"I don't know what this master plan is going to say, because I'm not a master planner," Mr. Voelker said.

The lack of a redevelopment plan and the state of the city's ruined neighborhoods have some worried that the city government has lapsed into the pattern of inactivity for which Mr. Nagin was criticized before last month's election.

"The city desperately needs leadership on planning and housing issues," an editorial in The Times-Picayune said last week. "Without strong guidance from City Hall, crucial decisions about the future of New Orleans will be made by default. Or they won't be made at all."

In occasional public appearances, the mayor has voiced characteristic optimism. "Today is another great day in the city of New Orleans," he said Wednesday after the A.F.L.-C.I.O. announced a $700 million housing and economic development grant. He called the grant "an incredible tipping point," but offered no specifics about which neighborhoods he was committed to rebuilding.

The mayor's flurry of appearances before the election has been sharply curtailed. Streets remain abandoned, sometimes for miles, and blocks are carpeted with trash.

"We do need to have a clear vision from the mayor," said Oliver Thomas, the president of the New Orleans City Council. "Tell us what you're for, or not for. We don't know exactly what neighborhoods he's committed to, kind of committed to, and not committed to."

Mr. Thomas added, "We don't know specifically what the roles of the neighborhoods are going to be in the new New Orleans. Can people build anywhere? Can they live anywhere? Are they going to be funded? We don't know that."

In the absence of a redevelopment vision from the city, residents are pushing ahead on their own, a process likely to be accelerated late this summer when washed-out homeowners begin receiving checks from the federal housing money appropriated by Congress. Whether homeowners who are rebuilding in ruined areas will remain isolated pioneers or will receive city services is still unclear.

A few badly damaged neighborhoods have undertaken their own planning efforts. "The initiatives for planning and rebuilding are coming from the neighborhoods themselves," said Pam Dashiell, a member of the Holy Cross Neighborhood Association, in the city's Ninth Ward.

The Broadmoor district, with a mix of incomes and races, has plans for converting abandoned dwellings to community use and wants to provide housing incentives for police officers and firefighters.

But few neighborhoods are as far along, and none of the efforts are being centrally coordinated.

During the recent election campaign, Mr. Nagin and most of his rivals carefully avoided pronouncements on the fate of specific neighborhoods, tiptoeing through a volatile issue that had many residents on edge. But now, critics say, the mayor does not have politics to use as an excuse.

"The election is over, and it's time for governing," said State Representative Karen Carter, Democrat of New Orleans. "He's the mayor, and he has to show that level of leadership and engagement."

Within a week of his re-election on May 20, Mr. Nagin announced that two ex-rivals from the campaign — both lawyers, one a Republican and the other a Democrat — would be aiding him in urgent planning for the city's future. In 100 days, there would be a plan, it was announced.

Since then nothing has been heard from either lawyer. One was traveling outside the country this week, and the other did not return calls.

In the interview on Friday, Mr. Nagin indicated that the entire city west of the Industrial Canal would be rebuilt, a more optimistic projection than some urban planners had given.

As for areas east of the canal, the mayor said that the prosperous New Orleans East area would probably come back and that the flattened homes of the Lower Ninth Ward would probably be replaced by what he called "multilevel living facilities," presumably apartment buildings.

Success, he said, is more likely to be defined by what residents do than what the editorial board of The Times-Picayune says. The city's current population of 220,000 is ahead of most projections, he said, and was made possible by his administration's willingness to provide building permits to almost all who asked, in any neighborhood.

"I think that most citizens can make intelligent decisions," Mr. Nagin said. "This city will be rebuilt. Most areas will come back. There are people who are rebuilding."

Mr. Nagin appears to be counting on a strategy that involves large-scale economic development projects, like one unveiled two weeks ago that called for demolishing a decrepit downtown shopping center and the city's frayed municipal complex and replacing them with a National Jazz Center set in a 20-acre park. Such development promises, largely unfulfilled, were a feature of Mr. Nagin's first term in office.

As for the planning body created after the hurricane, the Bring New Orleans Back Commission, little has been heard of it for months. The commission's tough plan, unveiled in January and now apparently dead, called for a four-month building moratorium in the hardest-hit neighborhoods while they proved their "viability." Ultimately a new public agency would have been empowered to seize land in areas that failed the challenge, and the city's footprint was to shrink.

Mr. Nagin, in the face of a public outcry, almost immediately rejected the plan.

Ray Manning, a local architect who played a key role in early planning efforts after the storm and who was a co-chairman of the mayor's neighborhood planning committee, said this week that he had withdrawn from the process.

"I said I would not speak about this issue any longer," he said.

At a conference at Tulane University this month, Mr. Manning had harsh criticism for the lack of guidance from City Hall.

For his part, the mayor in a brief appearance before reporters this week said of the neighborhood planning process, "That's just about completed."

Naming Mr. Thomas, the City Council president, as a collaborator, Mr. Nagin said, "There's a structure we'll be announcing in the next day or so, and we'll move that forward." But Mr. Thomas responded: "I don't know what the structure is. We've talked about some possibilities, but nothing definitively."

Now, 10 weeks before the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, some residents are losing patience.

"We are entitled to hear something now," said LaToya Cantrell, head of the Broadmoor Improvement Association. "We've been waiting. It's nine months out. We need to know what's going on. We need to know what the process is. The center of my community has yet to return, and this is nine months out. This is ridiculous. This is frustrating."

Interestingly, we here have become complacent, as one might expect. I remember feeling really, really ANGRY about the lack of a plan months ago. Now, I feel fatalistic, as if we all knew this was coming and should have expected it. You on the outside may wonder why we don't DEMAND change, or why we don't change things ourselves. But when we witness NOTHING CHANGING, we feel defeated, not motivated. Plus, our mayor is a WORTHLESS TURD who has done NOTHING in the interest of his own comfort. One of the strongest arguments for his ousting was that he simply NEEDS A BREAK. He feels as defeated as we do! How can this man make it happen for us!?

It's like my brother said. What we really need is a BENEVOLENT DICTATOR WITH REALLY GREAT IDEAS. Help!

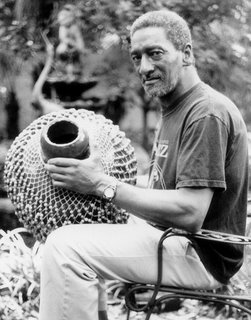

Here is more about Kufaru, in an obit written by Tracy of Kabuki Hats in New Orleans:

Sorry to announce the death of Kufaru Mouton, master

percussionist, of a heart attack in his home the

second week of June, 2006.

Born in NYC, he arrived in New Orleans over 25 years

ago on his way to Brazil (the country) and decided to

stay here, making his home base around Cafe Brasil on

Frenchmen Street, where, with Ralph Gibson, he played

the first gig at that venue many years ago. He

embodied the spirit of the Frenchmen Street music

scene, where he could be found playing or sitting in

on any given night of the week.

He studied with the masters Babatunji Olatunji and

Chief Bey in the 60's in NYC, when he was initianted

and was given the Santaria name of Kufaru, which means

Guardian. Kufaru was indeed the guardian of the craft

of the Conga drums, and spent years handing down the

tradition when he taught N.O. schoolkids in programs

like Young Audiences, and most recently the school

program run by The House of Blues International.

Back in NYC, Kufaru played briefly with The New York

Jets, and studied and taught African Dance, which he

continued here in New Orleans with the collective

Kumbuka.

Kufaru played and recorded with some of the best, and

his talent was in high demand. He was recorded on the

Neville Brothers "Mama Africa" and played with Luther

Gray and Kenyatta Simon of Percussion Incorporated.

Other music collaborators include Fredy Omar, Andy

Wolf, Robert Wagner, Ralph Gibson.....and too many to

list here. He will be missed by countless musicians

and music lovers who were lucky enough to experience

the magnificent stage presence he had, the powerful

talent and his love of people.

Kufaru could be found drumming till sunrise each Mardi

Gras, adding to the Carnival spirit that evolved on

Frenchmen Street each year outside of Cafe Brasil. His

music touched many hearts,and he played with true

dedication and joi de vivre.

A second line parade will be held on Monday, June 26th

at 6pm. at the corners of Dauphine and Piety Streets

in the Bywater, at the new coffeeshop owned by fellow

musician Andy J.Forest.. The Storyville Stompers will

lead the parade Cafe Brasil at the crossroade of

Frenchmen and Charters.

Please send written rememberances of Kufaru to

tracy@kabukihats.com, to be posted on an upcoming

website dedicated to the life and work of Kufaru

Mouton.

As Kufaru would say.....Peace.

Ashe, and thanks, Tracy

Kabuki Hats

Thursday, June 15, 2006

My dear friend Kufaru Mouton has died. I found out via an email before going to teach my 8 AM composition class. My students were putting on their best pathetic faces (they have an essay due tomorrow), and I wanted to shake their shoulders and tell them to get over themselves. Instead, I gave them a handout and instructions for peer review and cried my way back to my office, where I am trying to write about Kufaru.

I met Kufaru through another New Orleans friend who has,as they say here in NOLA, "passed on." Sam and I were living together and we both had a fondness for the bar I would later manage, The Dragon's Den. We went nearly every Friday to hear live music. Kufaru played in a reggae band called The Revealers. Actually, I don't know if it was Sam who introduced us--Kufaru and I would later have many, many friends in common because of our separate but intersecting roles in the New Orleans music scene--but I do remember that after Sam's suicide, Kufaru was very distraught. One night Los Vecinos was playing and Kufaru was sitting in on percussion. That night, Kufaru and I (perhaps having had one too many Johnny Walker Blacks [Kufaru] and tequilas [me]) closed down the bar together. Both he and I felt sure that we saw Sam dancing in the corner.

In our early days of friendship, we would hang out in his apartment above Checkpoint Charlie's, listen to music, smoke, and talk. He worked too hard--as did Chuck, and my dear old friend, Willie Metcalf, but he HAD to work. In addition to playing percussion in several bands, he cleaned the bar filth at Checkpoint for discounted rent, and later moved equipment at the House of Blues. He was tired often, and said so, and he made self-deprecating comments about being old. On his 50th birthday, I remember thinking that he looked much, much older than 50. I made him a carrot cake with cungas on in that said, "Happy Birthday, Knucklehead!" I can't remember now why I called him my knucklehead, but there it is.

It was difficult for me to remain close to him, though, because of his perpetually hitting on me. His advances were always harmless, so to speak, and I turned him down gently, but persistently, and I think I grew tired of his backrubs that sometimes wandered. I felt adored by him, and I knew he would not hurt me, but I hung out with him less, as a result.

But our spending less time together meant that our meetings were happy ones. I fed him Johnny Walker so he would close with me at the Den, and he told me stories about being underpaid, about his plans. He wanted to be able to support himself with his music.

It must have been four years ago, maybe three, when Kufaru had a heart attack and a stroke. I called him in the hospital and he asked that I not visit. This vigorous man--once a professional ballet dancer, later a soldier, now a working musician in New Orleans--seemed to know that he would have to slow down, and he didn't want those of us who knew him so alive and so active to see it happen.

The next time I saw him he was noticeably weaker. The House of Blues covered some of his medical expenses, but the stress of the hospital bills--and later of all of the medication he had to take--had a remarkable impact on him. He never really recovered. He had to stop drinking, which was really hard for him, and he could no longer perform his duties at the HOB because of the strain. He still called himself my knucklehead, and when I saw him and asked how he was he still said, as always, "I'm better now!"

I will remember perhaps best of all a cruise we went on together to Mexico. He was playing with the cruiseship's house band, Los Vecinos, whose lead singer, Manny, was an obnoxious prick. I think I endeared myself to Kufaru by standing up to Manny. Manny has a picture of me that he later said was "his favorite." In it, my face is obscured by a big ol' bird--the middle finger. I remember sitting on the balcony of a bar in Tulum, eating ceviche, drinking Sol, and telling Kufaru to quit staring at my boobs. I made him laugh, and his admiration, even when it was more than what I wanted, made me feel appreciated and loved. It wasn't just my boobs is why. I could shoot birds, burp, cuss like a sailor, call him my knucklehead, behave badly, and regret and he forgave me for my flaws. He loved me for them, I think, and I, him. (But what were his flaws? Loving too much? Working too hard? Not wanting to stop doing the salsa? Drinking?)

Kufaru was life, life, life to me. He was one of my first and best friends in New Orleans. I hope that wherever he has "passed on" to, I'll one day see him there. Him and Sam. Kufaru will have endless salsa partners, Sam will have decided to live, instead, and I will love them both: my knuckleheads. When we see each other, we will say, "I'm better, now," and it will be true.

I will miss you, Kufaru. I miss you, already. Here's to endless afternoons, high-paying gigs, and one last dance.

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

I met Chuck several years ago when I was managing and bartending at the Dragon's Den. At the Dragon's Den, and indeed all along Frenchman Street, we knew him as Edward. I don't know why we called him Edward, when his name evidently was really, actually, Chuck. Maybe he told us that was his name. Maybe someone accidentally called him Edward and he was too timid--but no, he wasn't timid--too kind to correct them. And he was, Chuck/Edward, he was really very kind.

I met Chuck several years ago when I was managing and bartending at the Dragon's Den. At the Dragon's Den, and indeed all along Frenchman Street, we knew him as Edward. I don't know why we called him Edward, when his name evidently was really, actually, Chuck. Maybe he told us that was his name. Maybe someone accidentally called him Edward and he was too timid--but no, he wasn't timid--too kind to correct them. And he was, Chuck/Edward, he was really very kind.Chuck died two weeks ago from AIDS, a fact I learned from a mutual friend who once belonged to the New Orleans Bayou Steppers--a Social Aid and Pleasure Club Chuck convinced me to join. Evidently he ended up in the Superdome after the evacuation, and there he was unable to get his medication and fell ill. He died in the home of his relatives, somewhere in California. I like to think that he was with loved ones, but I don't know. He never mentioned his family. I think he would have wanted to be in New Orleans, among friends. I think this place was his family.

But I need to tell you about Chuck.

The first time I met Chuck I was struck by how a)old he was (he must have been in his seventies) and b) how sharply--and "youngly" dressed he was. One might have described his attire as "pimped out," or in a derogatoy sense, thuggish. But he was no slave to the wrecks that sometimes get sold at Soul Train fashions--T-shirts emblazoned with cartoonish dudes with giant 'fros, yellow pin-stripe suits with gold threading, mock-italian shoes in shades of red, green, or maybe purple.

No; although Chuck's attire always matched, and was certainly distinctly black-fashion, he always dressed tastelfully--a fact in which he took great pride. He would pair a camel-colored mesh Kangol with a muted-colored striped polo shirt, dark-rinsed, low-slung jeans, and olive-toned Vans or boat sneakers. He'd take his hat off and put it on you at the bar and say, his eyes closed, "Baby, you look good in that hat. I'ma getchu a hat like that." He'd pull you to his tiny frame with his thin arms, and say it again, "I'ma getchu a hat."

He was always talking about gettin' me a hat, so that each time I saw him he'd say, "Baby, I haven't forgotten about yo' hat," and I would say, "Yeah, yeah, Baby, Baby, Baby--I'll believe it when I see it." I teased him for trying to come on too strong, but I never felt threatened by him, and when I told him, with a smile, to keep his hands to himself, he would smile and laugh and leave you with his cologne. He smelled good.

Sometimes Chuck did, in fact, dress in hip-hop attire--Fubu, Ecko, etc.--and it was then that his attire and his age seemed almost comical together. He sported unlaced Nikes with fat tongues and laces, or a single Roca-Wear sweat band on his wrist. Sometimes he wore a black nylon doo-rag instead of a Kangol ('though thankfully not the "mullet" kind, with a long neck-cover in the back.) You'd see this seventy-plus year old man--a tiny man, at that--no more than 5' 5", and skinny, skinny, skinny, riding a tricked-out bicyle to his cleaning job at the Blue Nile on Frenchman Street. If you called after him, his age would show. He couldn't hear very well.

I know very little about Chuck, which made learning of his illness even more of a shock. I'd heard once that he did smack, but it was not a rumor I cared to make inquiries into. I have lost two friends to heroin, and the mere mention of the drug makes me want to cover my ears and hide. I guess I am supposed to say that I should have cared about Chuck's drug habit, but he was lively, honest, and kind, and he seemed healthy. Had I asked about it, I think Chuck would have turned away from me. I didn't want that.

I know he lived in the Iberville housing project, and once I went into his unit with him. It was back when I was a member of the New Orleans Bayou Steppers--a racially mixed Social Aid and Pleasure Club that Chuck had convinced me to join, I thought, so he could "roll with me" on second line day. He liked to be in the company of white women--of young and attractive white women--and that fact didn't escape me. It was that reason, in fact, that drove me to leave the New Orleans Bayou Steppers. The men were kind and respectful, like Chuck, but the group had become almost solely comprised of black men and white women, and that bothered me. I never told Chuck.

I remember Chuck's refrigerator was covered in photographs, and that he showed me around the two-story unit with no small amount of pride. It was like any family home, and it felt loved.

I can't remember who Chuck lived with, but I remember a young nephew who he introduced me to, proudly. The nephew acknowledged me casually but seemed uninterested. I wondered how often Chuck brought home young white women, and whether his family thought his circle of friends--a great number of them privileged whites--to be at all odd. I didn't ask. I did ask him if he liked his house, and he said it was all he knew, that he'd lived there for years and that yes, he liked it a lot. "Baby," he said, "It's all right."

He liked to tell stories about being an Indian when he was young. To be a Mardi Gras Indian is to garner repect and admiration in the black community. To be an Indian is to be part of a tradition with high social rank and regard. As far as I knew, Chuck was no longer an Indian, if he'd ever been one. Once, he brought a picture of two young boys in Indian regalia into the Dragon's Den. "That's me," Chuck said, pointing at the picture, again with his eyes closed (he often talked with his eyes closed.) "That's me when I was twelve." The boy looked nothing like Chuck, and given how old I estimated Chuck to be, I thought it highly it highly unlkiely that it WAS him. The photo was rumpled--perhaps intentionally to make it look aged--but when I looked at the back of the photo, I saw "1996 Olympics" and the Olympic rings printed in a pattern on the back of the photo--a Kodak sponsorship deal. "Cool," I said to Chuck. "That's cool."

He liked to tell stories about buying you hats, and being an Indian. About rolling through second lines in genuine leather shoes, taking no breaks, looking sharp, continuously. About who he wanted to be, who he wanted to have been, who he wasn't. In retrospect, I guess it could be considered rather sad.

But Chuck was no "has-been." He was the genuine article, even if by "genuine" I mean little more than his facade, his "character": pimped out at 70-something, smooth-talking, and yes, a damn good "roller" when it came to a second line. He was something of a novelty to us privileged white bartenders on Frenchman Street--our tiny, geriatric thug--but what we admired about him, I think, is what we would admire in anyone: his desire to be someone. And he was someone--someone you wanted to be friends with.

What I will remember most fondly about Chuck is being called his Baby, and the way he would laugh, and keep at it, when I said to him, jokingly, "Do I look like a baby to you?" What I will remember is his talking with his eyes closed, and how I wondered what it was he really saw when he looked at me.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

On this, the first day of Hurricane Season, and the day of the inauguration of Ray Nagin--just over a week after Simon and I were married and voted, together, for hope and for change--I'd like to express my extreme sense of embarrassment at the re-election of our mayoral clown. Many of my friends at www.nolafugees.com supported this mayor, for reasons that I wholly disagree with. Here's an outline of what I believe to be the popular beliefs that drove Nagin and Landrieu voters to the polls, and a description of the political climate during the past several weeks.

On the night of the primary, Simon and I gathered at Handsome Willy's--a bar in the grim hospital district that regularly hosts Nolafugees events. By the time we arrived, the returns were already in. Our woman, Boulet, received just 4% of the vote--a little less than we had expected but not surprising, nevertheless. We voted our conscience during the primary, but we knew that an educated woman touting moving UNO downtown and universal healthcare had no chance.

As expected, Nagin and Landrieu were headed for a runoff, and for whatever reason I thought that surely my friends would agree with me. It was time for a change, I thought. Nagin had lost all credibility in the eyes of preceisely the people we would need most to help us rebuild: the national audience. While he had fussed up a storm during the aftermath of Katrina, eliciting "Amens" from all of us New Orleanians, myself included, his poor choice of words in his "Chocolate City" speech, along with his defensive and dismissive rhetoric that reminded me Dubya-talk, AND the fact that he had become the butt of jokes on the late shows and the subject of skits on Saturday Night Live, were SURE signs that this man had become a laughing stock.

What we needed, I believed (and I still believe) was someone with credibility. Someone who understood realpolitik--the need to participate in the legislative process in order to get things done. Someone liberal (Nagin supported Bush and Jindall). Someone who would demonstrate to the nation that we, the people of New Orleans, WANT to be takem seriously--and that we WANT to have a mayor who prepares for the inevitable Next Big Storm.

But that night I heard my friends saying things like, "I just can't bring myself to vote for a white mayor," and, "I won't vote for someone who belongs to a political dynasty." I could relate, to a certain extent, to the former content. It has been decades since New Orleans had a white mayor--and it's important, yes, that we have a mayor who represents the interests black majority.

But Nagin is a businessman. And practically a republican. And here he was, post-Katrina, pandering to the same black consituents whose needs he had NEGLECTED (resulting in DEATH). To neglect to provide for the needs of the poor during the evacuation was a TOTAL FAILURE, as they say, of the imagination. A fatal error. The scenario that we watched on television was NOT an unexpected one. In fact, if you read the Times-Picayune's "Washing Away" series, you will see the scenarios of desperation, suffering, and death, described with frightening accuracy. Nagin's failure to plan for this eventuality is a disgrace, however difficult it would have been for "whoever was in office," as so many are keen to point out. Nagin, who seemed to be touting himself as a populist candidate (his horrific and incredibly ironic "Re-elect Our Mayor, Re-unite Our City" billboards come to mind) had betrayed the same people whose behalf he claims now to be acting upon. Hmph.

As to the former comment, that my friends could not vote for Landrieu because he belongs to a political dynasty--, I too, can relate to that feeling. It's like my brother's voting for the Green Party in the 2000 election. He believed that if we supported the two-party system, a third party would never be created. Similarly, my friends believe that supporting Landrieu is saying that we are pleased with--and support--and often-flawed political process. I am not pleased with the shortcomings of the political process--with the often-unethical goings-on it seems to require. But...

But what we NEEDED to do was to vote in accordance with Realpolitik (as my brother did when he voted for Kerry in he 2004 runoff). Our idealistic intentions did not and do not matter, and if we are to survive in this city--if this city, itself, is to survive, we need the help of people whose PERCEPTION of our mayor drives the monies that will (or will not) now come our way. Landrieu--the real liberal candidate who, yes, is part of a well-connected political family--is perceived as an articulate, credible, and conscientious leader. Electing him would have demonstrated to outsiders that we understand the importance of outside help--that we understand that our local election has national implications that we are not ignorant of, that we cannot, realistically, simply thumb our nose at.

But a third argument, still, complicated these two arguments.

As I sat on the Mid-City porch of a friend's during Jazz Fest, Jarret of Nolafugees explained that he would vote for Nagin not because he was "the lesser of two evils," but because he was, in fact, more likely to fail than Landrieu. Landrieu's campaign had at its center a call for New Orleans to me a major American city in "the New South." His vision would have New Orleans competing with cities like Atlanta and Houston. One can imagine loft apartments taking over the projects, their former contents scattered to other projects--who cares? One can envision the kinds of rents we are now seeing in the city--rents like those in New York and San Francisco--for years and years to come. One can picture wider roads, bigger cars, fatter wallets, and less--much less-soul.

As someone from the capital of the New South, Atlanta, I can imagine this perhaps more vividly than Jarret or other young gentrifying whites like us who want the gentrification buck to stop here, with us. (Talk about privilege!)

I remember one night, during one of many blackouts (like the one we had again, just this morning), Simon and I were walking home from Mimi's, and in the moonlight the roof damage on my neighbor, Terrence's, home appeared cristalline, somehow; ragged. His home remains empty while Terrence lives in a small Houston apartment and calls me regularly, crying because he wants to come back to New Orleans. His landlord is a slumlord, and people like his parents, Gaynelle and Ronald, lack the resources to return. I looked at his house in the moonlight, and cried. I said to Simon, "There won't be any black people in our neighborhood anymore." Even now it makes my heart ache to think of--even as it comes true (much to the delight of many of my white neighbors.)

It is no wonder, then, that people like Jarret--and like me--would fear a New Orleans like Houston and like Atlanta--where money and privilege have bled the cities of their souls, have displaced their poor. But out of sight, out of mind, right? Oh, vapid, vapid Atlanta and Houston. Why would we want that here?

We don't. And I think, in fact, that Jarret's is the strongest argument in favor of Nagin. But still... To vote for FAILURE? Haven't we SEEN what the consequences of Nagin's failure? To vote for THIS?!

To be sure, Nagin has THE SAME vision as Landrieu. One need only read the report by the Bring New Orleans Back Commission to see that he, too, has a New South New Orleans in his sight.

And so, I guess, as we enter the next Hurricane Season--as we confront the possibility of a New South New Orleans--as we confront the probability of the poor and resourceless being once again, neglected--we must hope for a version of success that I cannot name. We must hope that this season is not a "When" season, but one of, "if, if, if." And we must resign ourselves, as I do, to a an uncertain future led by a man who has certainly failed us. We must, I suppose, hope for the f-ing best, and again, again, again, prepare for the f-ing worst.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)