Ha ha ha, Ho ho ho!

Ahoy to the World!

‘Twas the night before Christmas and in the Faubourg

At the edge of the crescent, no creature stirred.

Under the shroud-like blue plastic from FEMA

That flapped in the wind in the wake of Katrina,

Nothing was hung by the chimneys with care

Since chimneys and roofs were no longer there.

The houses, abandoned for trailers or Texas,

Were circled with watermarks, branded with Xs,

And in them no sugarplums danced in kids’ heads,

For no little children slept snug in their beds

On this night before Christmas in Faubourg-St John

Where time had stopped dead, while the world carried on.

Then, lo, from the depths of what once was my garden

(Now a wild cesspool of strange hydrocarbons)

Up drift some voices from out of the dark

To compete with the flapping of my FEMA tarp:

“They all axed for you, dawlin’. How did you do?”

“—Nine feet of water, and how about you?”

“Do ya know what it means to miss New Orleans?”

“—Not enough ersters—or rice and red beans!”

I‘m certain of whom this can’t possibly be:

It’s not the adjuster; it’s not Entergy;

With looters gone elsewhere, this can’t be a stick-up;

And who can remember the last garbage pick-up?

It’s surely not someone from Capitol Hill

To tell me, at last, whether I can rebuild.

I lift back what’s left of my old cypress shutters

And peek past the tangle of phone lines and gutters,

And what to my wondering eyes should appear?

Not Santa Claus and his team of reindeer

But, costumed in rubber attire and gas masks,

A long second-line waving hankies and flasks.

Rather than coconuts, beads and doubloons,

This krewe carries gear (and, just barely, a tune).

With wet vacs and power tools, sheetrock and nails,

Brawny and Brillo piled high in their pails,

They’re Superdome faithful, survivors of attics,

Mardi Gras maniacs, Jazz Fest fanatics,

Carnival trackers (from Allah to Zeus),

Believers in Saints (whether St. Jude or Deuce),

Joined by a couple of Dutch engineers,

Some out-of-town builders and church volunteers.

They pause at the dead Live Oak next to my door

In T-shirts declaring Make Levees Not War.

Since ditching my mold-ridden fridge at the curb,

MREs have become the hors d’oeuvres that I serve

So I pass them around with Abita’s new ale

When a wrench taps, “Clink! Clink!” on the side of a pail:

“To Blanco,” they cry, “She got contra-flow down!

To Nagin—he sure told those Feds and Mike Brown!

To NOLA dot com, CNN, and the Times

Who cut to the quick of the Superdome crime!

To all those who took in our downtrodden folks,

Or ferried them out in their flat-bottom boats!

To Tennessee… Texas… Jackson… Atlanta…

Our Baton Rouge brothers … and Lou-i-si-ana!”

I notice no Rudy steps up as their leader,

Yet something unseen guides this flock of believers,

A force that transcends rich or poor, black or white,

A light that can steer this brigade through the night.

In a twinkle they’ve finished the last of the ale

And they hoist their equipment, their masks and their pails:

“On, Comet! On, Borax! On, on Spic ‘n Span!

“Come (Yule) Tide and Cheer! Come, All, let us plan!

Up, Mildew! Off, Mold! Out, out, Toxic Waste!

Come, Shout! Away, Wisk! Come, let us make haste!

To the top of the water mark! Up, past the stair!

Let the City that Care Forgot know that we care!”

Then to Lakeview, Gentilly, Chalmette and the East,

Away they all marched to a Zydeco beat.

Ere they rose past the tarps, I heard a voice say

“Merry Christmas—and Laissez les bon temps rouler!”

Happy Holidays from Stephany New Orleans, 2005

Tuesday, December 20, 2005

Monday, December 12, 2005

The undertow

This editorial in Sunday’s New York Times gets it right. Even as we celebrated the holidays this weekend in our annual tree-trimming party, there was that same old undercurrent—it forreal floors you, how much it hurts to know that we are being forgotten.

Thursday, December 08, 2005

The drive to work these days.

Today I drove to campus for the first time since this summer, when I was teaching one section of freshman composition, when one of my students called me "Miss Chewbacka" because the new Star Wars had just come out, and when Tropical Storm Cindy was the big news, with her 80-mile-per hour winds and 15-hour power outage. (The day after Cindy I drove to get coffee at the only open coffee shop and was charmed by the camaraderie shared in the long line for espresso.) In other words, it was a lifetime ago.

I think I've mentioned before that one of my Uptown friends refers to the dry, and mostly white area of town that hugs the Mississippi River as the "Isle of Denial." One needs only to drive North or East to see what the rest of the city is like. And, in doing so, one realizes why one would rather live one's life solely on The Isle.

I hadn't cried in perhaps a week, maybe longer, but driving my regular commute for the first time since the storm--up Franklin and left at Robert E. Lee to the University--those tears came back, and hard, like I was making up for lost time.

I used to fantasize about buying a house in the neighborhood where Tom and Brandi had just settled in before Katrina. Gentilly was a primarily-black suburb of New Orleans, and its houses were mostly cozy ranches on piers. There was one house I liked, in particular, that was for sale last year. It had a kind of Spanish Bungalow flair to it, with stucco siding and red awnings, but it wasn't in very good shape, and anyway, buying is, for me, a pipe dream with all the debt I've got (I'd better not go there, or I'll start crying anew!)

Now, that house, and most of the houses on my commute, bears the watermark-scar of the flooding that, if one imagines sitting inside (as one would do in a house there--sit inside with family and friends, and eat and share, just as we had sat and eaten and shared in Tom and Brandi's house three weeks before the end of August,) would cover one's head.

I have these images now. It's not "seeing things," exactly; it's something else. It is as if my post-Katrina memories have superimposed themselves on the pre-Katrina ones. Now, when I recall memories of experiences I had in the areas that flooded, it feels like I’m looking at an insect preserved in amber.

I’d been down Franklin before, but now it looks worse. The gutting has begun. The signs have taken over. One that I saw today read, “We Demolish Houses.”

So I cried when I saw the house I once dreamed about owning, and I cried when I passed the intersection of Franklin and Gentilly, where the ridge saved the big houses and patches of green grass appear almost ridiculous, laughable. To have to mow one’s lawn in such a place! I cried when I saw FEMA trailers parked in front yards. I cried when I realized I was on auto-pilot, steering clear of the same potholes, the same sunken slabs of what passes for New Orleans’ streets (oh, to have THAT complaint NOW!) I cried when I saw the Sav-A-Center, where I once made all of my grocieries—how its parking lot has become a staging area for contractors and their equipment. I cried when I saw the once-majestic pecan trees along Robert E. Lee, the ones where I’d often seen old men with brooms banging the branches and collecting nuts in plastic shopping bags—the trees now splintered and nearly-bare (why is it that we always call big Southern trees “majestic”?)

At any rate, it was all one cry, but each of these markers seemed worthy of its own, good mourning.

I shaped up once I saw the signs for “Bush-Clinton Katrina Fund Event Parking.” They seemed so, well, weird, posted there next to signs for home demolition, but there they were.

I parked in the Engineering Building’s parking lot and walked to the quad in front of the library. I’ll admit it: my spirits lifted, pep-rally-style. There was a big, white, event-tent, and the new UNO mascot, “Air Pierre,” was there, bonking around, looking silly.

I approached two English Department colleagues of mine, Gary Richards and Anne Boyd, who both lost their homes. They could see that I’d been crying, and when I explained the “commute,” Gary said, “It doesn’t take much these days, does it. He’d gone to see the movie Rent, which he said, “wasn’t even very good,” and he positively bawled. Anne said she, too, was having crying bouts. What a weepy town we are.

The event was crowded—standing room only, and I stood in the back, next to the ubiquitous UNO-event jazz band and in front of the press. After a 45-minute wait, Presidents Clinton and George H. Bush finally arrived, along with Governor Blanco and the “first ladies” of Mississippi and Alabama. The purpose of the event was to announce the distribution of 90 million of the approximately 100 million the Bush-Clinton Katrina fund has saved. What everyone talked about was how the money came “from all corners of the world,” and they also talked about the importance of education and faith. Not surprisingly, the money was being allotted to higher education and churches. I could do without the faith-based stuff, but whatever.

Afterwards I tried to catch a photo of Clinton, but only got one where he’s a tiny ant. I had to doctor it to even make him visible, but I just wanted to have proof of seeing him. Now sure why, exactly. This is the prick who turned his back on the genocide in Rwanda, after all. But today was about “spirit,” and it was effective, in that sense. I even had my picture taken with “Air Pierre” after hearing from the English chair, Dr. Schock, that my job MIGHT still be mine in the fall.

I feel strange, though, like I don’t have any say in the funds or the future or anything, really. I am still so stressed out that my neck hurts and I clench my jaw. I worry about the future commute, about driving through devastation every day… devastation that is and is not my own. What must that do to a person! What it is doing to me, now!

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Yet another loss...

My longtime friend, Dave Sobel, who plays drums for the New Orleans Klezmer Allstars, told me last night that he is leaving New Orleans. He and girlfriend Jenny Baggert will move to Brooklyn in six months. There, they will seize the opportunities afforded them—members of the Katrina Diaspora. Dave will be able to play with the dozens of New Orleans musicians who have moved to New York City. He will have gigs and money and the tourists and citizens of New York will revel in his talent, and reward him with cash. Still, I couldn’t congratulate him. Instead, I walked away.

I realize this may not reflect well on my character, but I am angry about the loss of New Orleans musicians to other cities. I mean, I am angry at the musicians, themselves, as well as at the cities now hosting them. Tim Green said that the city of Austin—yes, the city government, itself—has called him repeatedly and offered him more money than he could ever make in New Orleans to move to Austin. Cities like Houston, Portland, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco are now benefiting from our loss. The musicians, themselves, are benefiting from our loss. They are finally getting the recognition—and the pay—that they deserve. So why I am so MAD at them?

Last night I went to see the Rob Wagner Trio at d.b.a. Rob is one of my favorite New Orleans musicians—an amazing saxophone player and composer. He moved here from out of town maybe ten years ago and refined his playing and writing skills in New Orleans.

What Rob found here—a community of like-minded musicians, an endless supply of gigs (gigs that unfortunately didn’t pay well enough that he could give up his day job of writing computing software,) a culture that, I like to imagine, fed his music, fed his soul—is what hundreds of musicians like Rob have found, too. They moved here from other cities, contributed to the musical culture through their own music (many of these musicians have pushed the boundaries of jazz in New Orleans,) and now, they’re leaving. Rob Wagner, Nobu, Dave Sobel, Linnzi Zaorski, Devin Philips, Greg Schatz—these are just a few names on a very long list of one-time New Orleans transplants who have taken this post-Katrina opportunity to move up, to move on.

I guess I feel betrayed. How could they come and soak up whatever this city had to offer them only to move away when the city fell down? How will our culture recover without them?

Last night I said to Bru that one thing that struck me was how little the musicians who have left and are leaving seem to care about their audience. It doesn’t matter to them who’s clapping, who’s paying the cover, who’s tipping the band, as long as the money comes in. They simply want to make a living—the best living that they possibly can—as working musicians, whatever the audience.

But how could they prefer to play to New York audience—one filled with tourists and corporate types with fat wallets—an audience comprised of patrons able to pay to $20 covers each week, no problem? How could they prefer them to us? I guess that’s what it feels like to me. It feels like Dave Sobel is saying, “Yeah, I had a great time here. Really learned a lot. But now I’m on to bigger and better things. Peace.” I feel like these musicians who have left and are leaving care more about their own future than they do the future of the city.

And the hardest part is knowing that we, the local music patrons of New Orleans, have evidently not supported our musicians in the manner that counts: in money. We have been spoiled by low-or-no covers, we have tipped in single-dollar bills. Our drunken declarations of appreciation are meaningless when it comes to making the musician’s life tick. We didn’t pay up.

As a one-time manager of the Dragon’s Den, where I booked music for several years, I knew we could charge more at the door, and pay more out of the register. I knew the musicians deserved better, but I didn’t own the place, and frankly, when I allowed the band to charge a higher cover, the patrons opted not to come in. Why would they want to fork over ten bucks when just down the street they can hear another band for free? How could we—the club managers—have made this city work for the musicians? How could we have prevented this mass exodus from occurring?

Perhaps more importantly, what can we do now?

Evidently, Harry Connick, Jr., and Branford Marsalis think this is the answer. They’d like to build a “musicians’ village” in New Orleans. I may be wrong, but I don’t think that housing is the real issue here. I think the real issue is how we have failed our musicians in the past, how other American cities are pouring on the sympathy—and the cash—and how there won’t be a population with fat enough wallets to support those musicians who do return. After all, the artists and educators, the working professionals, who were the ones who supported their careers (in cash), in the first place are losing their jobs, too.

I realize this may not reflect well on my character, but I am angry about the loss of New Orleans musicians to other cities. I mean, I am angry at the musicians, themselves, as well as at the cities now hosting them. Tim Green said that the city of Austin—yes, the city government, itself—has called him repeatedly and offered him more money than he could ever make in New Orleans to move to Austin. Cities like Houston, Portland, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco are now benefiting from our loss. The musicians, themselves, are benefiting from our loss. They are finally getting the recognition—and the pay—that they deserve. So why I am so MAD at them?

Last night I went to see the Rob Wagner Trio at d.b.a. Rob is one of my favorite New Orleans musicians—an amazing saxophone player and composer. He moved here from out of town maybe ten years ago and refined his playing and writing skills in New Orleans.

What Rob found here—a community of like-minded musicians, an endless supply of gigs (gigs that unfortunately didn’t pay well enough that he could give up his day job of writing computing software,) a culture that, I like to imagine, fed his music, fed his soul—is what hundreds of musicians like Rob have found, too. They moved here from other cities, contributed to the musical culture through their own music (many of these musicians have pushed the boundaries of jazz in New Orleans,) and now, they’re leaving. Rob Wagner, Nobu, Dave Sobel, Linnzi Zaorski, Devin Philips, Greg Schatz—these are just a few names on a very long list of one-time New Orleans transplants who have taken this post-Katrina opportunity to move up, to move on.

I guess I feel betrayed. How could they come and soak up whatever this city had to offer them only to move away when the city fell down? How will our culture recover without them?

Last night I said to Bru that one thing that struck me was how little the musicians who have left and are leaving seem to care about their audience. It doesn’t matter to them who’s clapping, who’s paying the cover, who’s tipping the band, as long as the money comes in. They simply want to make a living—the best living that they possibly can—as working musicians, whatever the audience.

But how could they prefer to play to New York audience—one filled with tourists and corporate types with fat wallets—an audience comprised of patrons able to pay to $20 covers each week, no problem? How could they prefer them to us? I guess that’s what it feels like to me. It feels like Dave Sobel is saying, “Yeah, I had a great time here. Really learned a lot. But now I’m on to bigger and better things. Peace.” I feel like these musicians who have left and are leaving care more about their own future than they do the future of the city.

And the hardest part is knowing that we, the local music patrons of New Orleans, have evidently not supported our musicians in the manner that counts: in money. We have been spoiled by low-or-no covers, we have tipped in single-dollar bills. Our drunken declarations of appreciation are meaningless when it comes to making the musician’s life tick. We didn’t pay up.

As a one-time manager of the Dragon’s Den, where I booked music for several years, I knew we could charge more at the door, and pay more out of the register. I knew the musicians deserved better, but I didn’t own the place, and frankly, when I allowed the band to charge a higher cover, the patrons opted not to come in. Why would they want to fork over ten bucks when just down the street they can hear another band for free? How could we—the club managers—have made this city work for the musicians? How could we have prevented this mass exodus from occurring?

Perhaps more importantly, what can we do now?

Evidently, Harry Connick, Jr., and Branford Marsalis think this is the answer. They’d like to build a “musicians’ village” in New Orleans. I may be wrong, but I don’t think that housing is the real issue here. I think the real issue is how we have failed our musicians in the past, how other American cities are pouring on the sympathy—and the cash—and how there won’t be a population with fat enough wallets to support those musicians who do return. After all, the artists and educators, the working professionals, who were the ones who supported their careers (in cash), in the first place are losing their jobs, too.

Monday, December 05, 2005

This should be good...

ROB WAGNER/HAMID DRAKE/NOBU OZAKI at D.B.A. (618

Frenchmen Street) 10PM Monday Dec. 5

Rob Wagner, saxophones and compositions

Hamid Drake, drums

Nobu Ozaki, bass

"All events that don't appear in the media are claimed

as a victory by the movement . . ."---The Anti-Media

Movement.

At first I was quite peeved that our local guardians

of the fourth estate could not find the significance

of this event worthy of their precious media space

(and their less than precious efforts,) but than I

realized that if they had, how significant could have

it ever been? The best of New Orleans culture has

always hidden in plain view, shielded by its apparent

extravagant ubiquitousness.

But we know how to see (hear) beyond the mask, and we

will talk to each other face to face, immediate as

wind and water, and spread the word. And this event

will be a great success, appreciated by all who manage

to attend . . .

Benjamin

P.S. I'm told by the Powers That Be that this concert

will start at 10PM N.R.T. (New Realities Time) not

10PM S.N.O.M.T. (Standard New Orleans Musicians' Time)

so plan your arrival accordingly.

VALID RECORDS "Valid Where Prohibited!"

--from an email sent to me by Bywater resident and fellow music lover, Ben Lyons

ROB WAGNER/HAMID DRAKE/NOBU OZAKI at D.B.A. (618

Frenchmen Street) 10PM Monday Dec. 5

Rob Wagner, saxophones and compositions

Hamid Drake, drums

Nobu Ozaki, bass

"All events that don't appear in the media are claimed

as a victory by the movement . . ."---The Anti-Media

Movement.

At first I was quite peeved that our local guardians

of the fourth estate could not find the significance

of this event worthy of their precious media space

(and their less than precious efforts,) but than I

realized that if they had, how significant could have

it ever been? The best of New Orleans culture has

always hidden in plain view, shielded by its apparent

extravagant ubiquitousness.

But we know how to see (hear) beyond the mask, and we

will talk to each other face to face, immediate as

wind and water, and spread the word. And this event

will be a great success, appreciated by all who manage

to attend . . .

Benjamin

P.S. I'm told by the Powers That Be that this concert

will start at 10PM N.R.T. (New Realities Time) not

10PM S.N.O.M.T. (Standard New Orleans Musicians' Time)

so plan your arrival accordingly.

VALID RECORDS "Valid Where Prohibited!"

--from an email sent to me by Bywater resident and fellow music lover, Ben Lyons

We do what we can.

Last night I went to see 3 Now 4 at d.b.a. and saw Tim Green for the first time in a long while. Tim Green is positively the best saxophone player there is. He played sax with the Hi-Life Rescue Dance Band back four years ago, I guess, and I remember how happy I was to sing with someone who was so attentive to the group dynamic. He and I had a call-and-response, uh, "jam," and I was at that moment forever endeared to his playing.

I remember driving back to New Orleans from a gig we had in Lafayette. At the time I was volunteering for WRBH, 88.3 f.m. (Radio for the Blind and Print Handicapped,) and he talked about his tenure there and as station manager for WWOZ. He also talked about leaving his work in radio to work as a full-time musician. I was struggling with my own decisions. I'd just started graduate school and was singing with Hi-Life and bartending at the Dragon's Den and volunteering, and I didn't know what I really wanted to pursue. I can't remember what Tim's advice was, exactly. I don't think it was radical. Something along the lines of following one's heart, I think. At any rate, I just remember thinking that this was one righteous dude, so to speak. He's got the patience and wisdom thing down.

Tim sounded great. He was playing a crazy horn with what looked like the world's smallest diving mask attached to the bottom. At the set break he told me that someone gave it to him while he was in San Francisco after the storm--just walked up to him and said something like, "You should have this." It's appearently called a conosax and is one of only 12 in the world. It's worth $42,000. Anyone else and I would think that San Fran man was crazy, but I can absolutely understand feeling compelled to endow Tim Green with such a gift.

Tim looked great, too. Bru (from Hi-Life) and I agreed--he looks younger and happier than we'd seen him in a long time. Tim attributed it to his being happy to be home. I squeezed him too hard. I got tears in my eyes. After hearing that James Singleton is gone--even if he IS coming back once a month for gigs--after hearing that Rob Wagner and Schatzy and Jeremey Lyons and Devin Phillips and Nobu and so many, many, many musicians are not planning to come back, I was beginning to feel that our musicians would all abandon us.

I told Tim about a quote I read in this week's Gambit. Playwright Richard Read said, "We're all mouthing the same thing: 'Oh, we certainly don't blame anyone who has to leave; people lost jobs and homes.' But the emotional side of it is, 'Why don't you people move back? This is a great time to make things happen in the city.'" We—Tim, Bru, and I—all agreed that it’s hard not to be angry, to feel a little abandoned by folks who’ve decided to leave—especially the musicians, but we really can’t blame them.Tim said there are lots of gigs here, that he’s playing all the time, solid.He said he wants to be here; that in Algiers, where his home it, life is good—so good that it can be hard to stay motivated to work on the recovery, but he sends out emails and he does what he can.Oh, and when he As long as there is music, there will be some semblance of hope.

Tim also told me about 88.7 f.m., which is being run out of Algiers by IndyMedia.org.nbsp; I turned it on this morning, and it was like a fucking revelation. The music is commercial-free, uncensored, and fantastic. I heard old De La Soul and new Kanye West and Lauren Hill and Irish protest songs, and all kinds of music for revolution. Plus, Tim says that the radio staff goes out with microphones and collects people’s stories. They also announce resources. I couldn’t help laughing when I heard this one: “A free clinic is available for treatment at preventative medicine at Mardi Gras World.” A free clinic at Mardi Gras World! Oh, the things we DO when we do what we CAN!

Thursday, December 01, 2005

Why I am a coward.

Here Miss Diane sits on Miss Grace's stoop. This was back when we first returned to New Orleans--back before she'd been evicted.

I am grading students essays, trying to find ways of telling my students why an audience might not appreciate a female dog being referred to in an essay as “my bitch” or a car as an “automated vehicular contraption” when I am interrupted by one of the many new noises of the neighborhood. I have become used to the Red Cross mobile’s cop-horn and the once-regular but now sporadic rumbling of Humvees and scraping of Bobcats, but this noise was a banging I’d not heard. I peak out the slats of our shutters and see a big and sparkling Cadillac, and behind it a locksmith’s truck. It is Miss Diane and Miss Grace’s former landlord, and she is having their locks changed. I want to fucking kill her, and I mean it; I have not felt rage like this since I can remember.

Yesterday, Miss Diane and Oscar came by their old house—the house with new locks—to survey the work that had been done. Weeks ago they were evicted. A terse letter informed them that “due to extensive storm damage to the property,” they and Miss Grace next door would have to vacate the home. The landlord said she expected to perform the repairs and would contact them once completed. The extensive damage was, in fact, minor roof damage. The work that has been done: locks have been changed.

A week ago I saw Miss Diane and Oscar sitting in front of the house. They were both crying. Yesterday, Miss Diane said she was ready to report their landlord to Channel 6’s investigative reporter, Richard Angelico. Miss Diane, Oscar, their 30-year-old son with severe cerebral palsy, and their 15 year-old, Oscar, Jr., have been living with Miss Diane’s daughter. They had to give up their dogs because her daughter wouldn’t allow them. Every day they spend an hour driving into town. Oscar lost his job of 24 years to “some Spanish guy” who doesn’t know printing press work and who Oscar suspects is getting paid pennies on his dollar. Their rent at the house across the street was $390/month. Now, you can’t find a place in this area for less than $1,000. It is gay-town, Cadillac-town, white-town; we don’t have room for the Miss Dianes in the Marigny anymore.

A week ago I saw Miss Diane and Oscar sitting in front of the house. They were both crying. Yesterday, Miss Diane said she was ready to report their landlord to Channel 6’s investigative reporter, Richard Angelico. Miss Diane, Oscar, their 30-year-old son with severe cerebral palsy, and their 15 year-old, Oscar, Jr., have been living with Miss Diane’s daughter. They had to give up their dogs because her daughter wouldn’t allow them. Every day they spend an hour driving into town. Oscar lost his job of 24 years to “some Spanish guy” who doesn’t know printing press work and who Oscar suspects is getting paid pennies on his dollar. Their rent at the house across the street was $390/month. Now, you can’t find a place in this area for less than $1,000. It is gay-town, Cadillac-town, white-town; we don’t have room for the Miss Dianes in the Marigny anymore.I want to scream at the bitch who’s having their locks changed. Miss Diane says she’s a lawyer, and judging from the looks of her, her Cadillac, and her Metairie accent, I suspect she’s the kind of lawyer we could all use less of. A lawyer whose motives are winnings, not winning. I hope she dies. Tomorrow. Today. Now. No—better than that, I hope she loses her job; I hope her kids get debilitating illnesses and have to rely on Medicaid; I hope she loses her home and has to stay with relative and has to give up her pets and has a bitch for a landlord who tells her she will repair the home but does nothing but change the locks.

And I want to say these things to her, but apparently I am a coward. I post pleas on behalf of my neighbors on online forums. I don’t confront bitch landlords who deserve to die. Evidently, it’s just not my style.

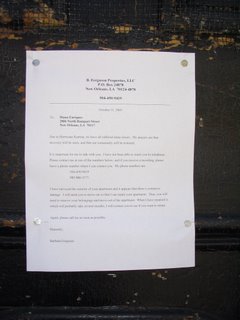

The bitch's words.

The bitch's words.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

November 22, 2005

Today the Red Cross mobile that passes daily began getting clever, which was a welcome respite, really from the cop-like horn and the grim announcements of “Red Cross has hot meals and water.” Today the honker rhythmically tapped the cop-horn and the announcer yelled “Yoo-hoo, Come and get it!” Still, I can’t help wondering if they don’t feel a bit silly riding around this repaired neighborhood—this mostly-unscathed neighborhood—this neighborhood where we are home and where Simon makes me meals like broiled salmon or roasted chicken and we drink Abita Restoration Ale to wash it all down. It seems off to me that the Red Cross was absent in the immediate aftermath, when people so desperately needed food and water, and that they then began closing shelters and centers in Atlanta and other areas where Nola evacuees are, and then here they are, in New Orleans, finally, where the population is mostly NOT one that needs formed, warm chicken part-patties and canned peas. Where there are over 50 restaurants open and jobs and where those who are homeless are mostly workers who camp in the park and get overpaid by FEMA for jobs or displaced residents should have. I heard on the local news today that of the 460,000 New Orleans residents who lived here before the storm, just 60-70,000 have returned.

I see other returnees in the Sound Café, where I went for coffee and to grade student essays this morning. T.R., my boss form Tulane, was there, and he asked how we were doing. It’s a hard question to answer. Last night I was so tense—and I am now, too—that I felt like someone was standing on my head. I feel like my jaw is constantly clenched. Still, I told T.R. that we were fine, all things considered; that Simon is not working; that he can’t work because he is “out of status”, until we get married. (I guess given that fact it’s no wonder that I am stressed. Not only do I have my own uncertain future to deal with, I also have to marry Simon before he can make the next step in his life.) And of course I want to marry Simon, but to marry him so he can get a job? I never wanted marriage to be a logistical solution. I never wanted my life to be so logistically uncertain, either.

What I wanted was for none of this to happen. I wanted to return from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and become a Real Writer. I wanted to have my new full-time job and my new benefits and my newfound stability. I wanted to have a romantic proposal and a romantic wedding and a long teaching career at UNO. I wanted to keep writing my stories about hurricanes—hurricanes that miss New Orleans. That was all I wanted. Stories with happy endings, duh!

And I don’t want these stories—stories of my writing a really corny letter asking my friends and family to write congress, to help save New Orleans. I don’t want to tell stories about the periodic power outages, or the woman at the neighborhood association meeting who claimed she felt like she was being treated like a jew in nazi Germany because of said outages. I don’t want to tell stories about the national guard’s Humvees or the wildfire-fighting trucks that are parked down by the performing arts high school—the same school that educated the Marsalises and is rumored to be slated for funding cuts. I don’t want to tell stories about eating MREs for fun or the green “smooth-move” chiclets that accompany them; about sleeping too much and having nightmares about watermarked buildings; of drinking too much and having drunken conversations about having nightmares about watermarked buildings.

I don’t want to tell any of these stories unless they come with happy endings. If they end happily, they will be the color of nostalgia rather than regret. They will have the character of memories that one wants to hold on to… of memories one regrets not recording. Otherwise, I will read this shit and will think if, if, if…

It is hard to have hope. On Thanksgiving Day, I had a (very drunken) conversation with a friend of mine, Arin, who, like me, was feeling powerless. When we were in Atlanta and volunteering for the Red Cross, it felt at least like we were connected to something. Here, I frankly don't feel much like leaving the house, and Arin and I talked about that feeling. Here, the Red Cross drives through the streets every day offering "hot meals and water," which they announce on a bullhorn, to people like me--people who really don't NEED the help. I don't want to do that work. I want to build things and influence people, and so I told Arin that what we, writers and educators, could do was write letters--to remind people that we need them not to forget us. I had written one such letter just a couple of days before, and it makes me cringe in its corniness, but it's heartfelt, at any rate, and here it is:

November 21, 2005

Dear Friends and Family,

In the six weeks since Simon and I returned to New Orleans, we have witnessed a lot of progress. The discarded refrigerators that once populated the sidewalks in front of nearly every home in our neighborhood have been removed, and along with them, the indescribable stink of their rotten contents. The coffin-flies—we’d foolishly been calling them “fruit flies”, a far too endearing term for the insatiable beasts—which once circled our heads with a third-world persistence and peppered fly-ribbons in nearly every home and business in New Orleans, have begun to die off in the cold weather that has arrived. Many of the abandoned and wrecked boats, buses, hearses, and cars that had congregated on the now-brown front yards and neutral grounds across the city have been hauled off to some unknown gravesite, and in their place, a few blades of green grass have begun to grow.

In our more immediate, daily lives, too, there has been progress. Three weeks ago, the gas was turned on. We took hot showers. We stored our Coleman stove in the backyard shed. Last week we received mail at our home for the first time—no more hour-long lines at the makeshift trailer park postal center downtown—although we have yet to receive a FedEx package my mother mailed two weeks ago. On Saturday, the Bobcats that trolled the streets for debris were replaced by a bona fide city garbage truck. (I have never been so tempted to embrace a man drenched in trash-juice.) The Chevron station at Elysian Fields and Claiborne finally has fuel. Our local coffee shop has wireless internet and fresh croissants delivered daily. And—blessing of all blessings—the Whole Foods in Metairie opened. We have grown accustomed to weekly power outages. We find comfort in the nightly rumble of Humvees. We swap FEMA stories and tell Brownie jokes. And, at least once a week, we dance.

But in spite of all this progress, it is impossible to ignore the slow pace of recovery in the parts of New Orleans that received the most damage. In the neighborhood of Gentilly, just to the north of us, where Simon’s brother, Tom, and his wife, Brandi bought a house just one month before the storm, there is no power, no water, and no one with answers. Although insured, Tom and Brandi have yet to receive word from their adjustor. Others with flood insurance have been told that because the flood was caused by levee failure, much of their losses will not be covered. I need not mention the plight of the uninsured. They, too, must wait to be told what’s next. And after weeks of benefiting from the attention and pity afforded them by the media, the hardest-hit residents of New Orleans are now, again, falling victim to the policies of a federal government with a short memory and a penchant for punishing its poor.

Certainly, it is difficult to know where to begin. If we rebuild, do we rebuild everything—even the areas that were once swampland prior to the 1950s and 60s? Or do we rebuild only in the city’s footprint prior to the construction of the levees? Can we consider rebuilding, even, when the levees are not constructed to withstand the inevitable—a Category 5? Why bother? If something like what has happened this year is going to happen again—in 100 years, 10,000 years, whatever—shouldn’t we organize an orderly retreat, instead? These are important questions, but they are the questions that are stalling our city’s progress. They are questions that have the federal government bickering, hedging, and finally, scolding us for living here.

But we live here. I live here. And I am committed to continuing to live here because, frankly, there is no other place in the world I can imagine living. Many of you have visited me here, and I think I can safely say that you all loved some part of our city. Whether we went to a Mardi Gras parade or a second-line, whether we visited the Southern Museum of Art or attended a tequila-tasting, whether we danced at Jazz Fest or late-night at the Dragon’s Den, you have all had an impression of what I am fortunate enough to enjoy year-round.

Still, it’s not the celebrations or the reveling, alone, that attracts me to New Orleans. It’s the other stuff, too. Call me crazy, but I like living in a place where I am not insulated from all that is ugly—from poverty, from neglect, from the threat of disaster. I like it not because I welcome these things, but because I cannot forget that they do, in fact, exist. Knowing this, being surrounded by it, makes me ache, but that ache makes me feel somehow more alive. As Garrison Keelor once said, in New Orleans we dance not because we feel good, but because we know it will help us feel better.

Unfortunately, our party-hearty attitude has hurt us. We grew fatalistic, complacent. We danced instead of doing anything, and now it seems that many people think we don’t deserve to dance again. A friend of mine said that living in New Orleans right now is like waking up every morning to the remnants of last night’s party. You feel so overwhelmed by the mess that you don’t know where to begin. It’s easier to mix a stiff bloody Mary and get comfortable, instead.

But we can’t get comfortable, and we need your help.

Below you will find an editorial published in Sunday’s Times-Picayune. While I’d give it an “A” in my comp-class, I find it came woefully late, and I worry that with the approach of the holidays, we will be forgotten. Who has time for writing senators when there’s turkey to be eaten, gifts to be bought? Who has time to forward emails and cut and paste letters to congress when the Christmas cards have yet to be addressed? And furthermore, who really wants to remember New Orleans when, well, it’s a real f-ing downer?

I never imagined that I would live through an event like this, and I certainly never imagined I’d have the opportunity to participate in the rebuilding of a great American city. Without getting all soapbox on you, let me just say that all of us—New Orleanians and Americans, alike, have a pretty awesome responsibility facing us. How we react to this will speak to our capacity not just to imagine the lives of others, but to act on that empathy. Remember us. Speak up for us. We cannot do it by ourselves; it’s clear by now that we have lost our credibility. We need you.

Please forward the Times-Pic editorial and the contact list that follows to your friends, coworkers, and family. If you are a teacher, ask your students to write on our behalf. Heck, give the kids some extra credit. Ask everyone to remember us during the holidays, and to send a card to Congress that asks for a new New Orleans for Christmas.

Yours,

Sarah

P.S. That is about the sappiest, corniest letter I have ever written. I’m darned emotional down here. Deal with it. ; )

An Editorial: It's time for a nation to return the favor

Sunday, November 20, 2005

The federal government wrapped levees around greater New Orleans so that the rest of the country could share in our bounty.

Americans wanted the oil and gas that flow freely off our shores. They longed for the oysters and shrimp and flaky Gulf fish that live in abundance in our waters. They wanted to ship corn and soybeans and beets down the Mississippi and through our ports. They wanted coffee and steel to flow north through the mouth of the river and into the heartland.

They wanted more than that, though. They wanted to share in our spirit. They wanted to sample the joyous beauty of our jazz and our food. And we were happy to oblige them.

So the federal government built levees and convinced us that we were safe.

We weren't.

The levees, we were told, could stand up to a Category 3 hurricane.

They couldn't.

By the time Katrina surged into New Orleans, it had weakened to Category 3. Yet our levee system wasn't as strong as the Army Corps of Engineers said it was. Barely anchored in mushy soil, the floodwalls gave way.

Our homes and businesses were swamped. Hundreds of our neighbors died.

Now, this metro area is drying off and digging out. Life is going forward. Our heart is beating.

But we need the federal government -- we need our Congress -- to fulfill the promises made to us in the past. We need to be safe. We need to be able to go about our business feeding and fueling the rest of the nation. We need better protection next hurricane season than we had this year. Going forward, we need protection from the fiercest storms, the Category 5 storms that are out there waiting to strike.

Some voices in Washington are arguing against us. We were foolish, they say. We settled in a place that is lower than the sea. We should have expected to drown.

As if choosing to live in one of the nation's great cities amounted to a death wish. As if living in San Francisco or Miami or Boston is any more logical.

Great cities are made by their place and their people, their beauty and their risk. Water flows around and through most of them. And one of the greatest bodies of water in the land flows through this one: the Mississippi.

The federal government decided long ago to try to tame the river and the swampy land spreading out from it. The country needed this waterlogged land of ours to prosper, so that the nation could prosper even more.

Some people in Washington don't seem to remember that. They act as if we are a burden. They act as if we wore our skirts too short and invited trouble.

We can't put up with that. We have to stand up for ourselves. Whether you are back at home or still in exile waiting to return, let Congress know that this metro area must be made safe from future storms. Call and write the leaders who are deciding our fate. Get your family and friends in other states to do the same. Start with members of the Environment and Public Works and Appropriations committees in the Senate, and Transportation and Appropriations in the House. Flood them with mail the way we were flooded by Katrina.

Remind them that this is a singular American city and that this nation still needs what we can give it.

Contacting Congress

Sunday, November 20, 2005

The fate of greater New Orleans' levees lies with the committees and lawmakers below. These leaders won't know how you feel about the need to upgrade greater New Orleans' flood-protection system unless they hear it from you.

Making contact can take a little effort. While some members have public e-mail addresses, others only accept e-mail via forms on their Web sites. However you communicate, use your own words, and speak from the heart.

SENATE MAJORITY LEADER

Sen. Bill Frist, R-Tenn.; 509 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-3344; Web site: www.frist.senate.gov.

SENATE APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE

Sen. Thad Cochran, R-Miss, chairman; 113 Dirksen Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-5054; e-mail address: senator@cochran.senate.gov.

Sen. Robert Byrd, D-W.Va., ranking member; 311 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-3954; e-mail address: senator_byrd@byrd.senate.gov

Sen. Ted Stevens, R-Alaska; 522 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-3004; Web site: www.stevens.senate.gov

SENATE BUDGET COMMITTEE

Sen. Judd Gregg, R-N.H., chairman; 393 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-3324; Web site: www.gregg.senate.gov

Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D., ranking member; 530 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-2043; Web site: www.conrad.senate.gov

SENATE ENVIRONMENT AND PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE

Sen. James Inhofe, R-Okla., chairman; 453 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-4721; Web site: www.inhofe.senate.gov

Sen. Max Baucus, D-Mont., ranking member; 511 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510; (202) 224-2651; e-mail address: max@baucus.senate.gov

SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE

Rep. Dennis Hastert, R-Ill.; 235 Cannon House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-2976; Web site: www.house.gov/hastert

HOUSE MAJORITY LEADER

Rep. Roy Blunt, R-Mo.; 217 Cannon House Office Building; Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-6536; Web site: www.blunt.house.gov

HOUSE APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE

Rep. Jerry Lewis, R-Calif., chairman; 2112 Rayburn House Office Building; Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-5861; Web site: www.house.gov/jerrylewis

Rep. David Obey, D-Wis., ranking member; 2314 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-3365; Web site: www.obey.house.gov

HOUSE BUDGET COMMITTEE

Rep. Jim Nussle, R-Iowa, chairman; 303 Cannon House Office Building; Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-2911; e-mail: nussleia@mail.house.gov

Rep. John Spratt, D-S.C., ranking member; 1401 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-5501; Web site: www.house.gov/spratt

HOUSE RESOURCES COMMITTEE

Rep. Richard Pombo, R-Calif., chairman; 2411 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-1947; e-mail: rpombo@mail.house.gov

Rep. Nick J. Rahall II, D-W.Va., ranking member; 2307 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-3452; e-mail: nrahall@mail.house.gov

HOUSE TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE

Rep. Don Young, R-Alaska, chairman; 2111 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-5765; Web site: www.donyoung.house.gov

Rep. James Oberstar, D-Minn, ranking member; 2365 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515; (202) 225-6211; Web site: www.oberstar.house.gov

Simon and I have been back in New Orleans for almost two months. During that first month, I barely wrote a word. I took lots and lots of pictures, instead. The following is the first entry I wrote. I hope that others will follow.

November 14, 2005

The power goes out again. This happens at least once a week, but there is no getting used to it. At times like these, the here and now feels startlingly immediate, and we try to focus on these things so we can deal with them: where are the flashlights, the candles, the matches? Whether we had plans prior to the loss of power is irrelevant, and I forget what it was I wanted to do anyway. I want light. I want the stove to work. I want my computer and the internet and a fan that I can turn on and leave on all night to ward off strange noises. Never mind that the neighborhood is quieter than it has ever been, that even the trains seem to have been interrupted. Every noise is odd now, even the familiar ones. You can’t really describe what’s changed, either. It’s as if you are seeing someone again for the first time in many years, and their looks are all still there, their appearances are arranged according to your memory, but perhaps they’ve adopted a new accent or gone religious on you. In either case, something happened while the two of you were apart, and even as you try to behave as you once did—remembering-when or re-telling a joke you once shared, the punchline thunks you in the gut, somehow. You laugh less heartily these days.

I point out to Simon that our flashlights are near dead and that our candles are at their ends. He knows I am blaming him. I have told him how silly I think it is to light up the house like a Catholic church in times like these. I tell him we need only light the room where we are right now. It’s true that I liked the way the house glowed the first night we lost power. We made boudin and red beans and rice on our Coleman stove, but back then the blackouts were a novelty—back then we all emerged from our homes to see if the neighbors had lost power, too. Back then we were convivial and maybe even grateful to know that we really were “in this together.” Now, though, I am angry because there is no one to blame.

My new laptop has three hours-worth of battery and so I sit down to get some work done. Simon lights about eight candles, then nine, and I snap at him for being wasteful. He says he refuses simply to sit in the dark and do nothing. He is not working these days, and six weeks into my semester, with midterms approaching and papers to grade, I, too, wish he wouldn’t “do nothing,” but I don’t want him to lounge around reading, as he has. I resent him for having the money and the time to do what I would like to do. It is hard to be in love right now.

While Simon goes out for a run, I call Entergy to report the outage. I ask the man at the end of the line when the power will return. “A ballpark figure will do,” I say, feeling sorry for the guy even as I ask—he who is burdened with the task of apologizing for things he can’t control. Even so, we’ve gotten ballpark figures before. They give us some small hope, even though by now we know to add an hour or two to the time reported to us. The man says he can’t offer one, and I think I hear annoyance in his voice, but find myself complaining anyway. “It’s just that I’m a teacher and it’s hard to get things done when the power goes out every time the wind blows even the tiniest bit.” He must be rolling his eyes. He must hate me. I hate myself. “Nevermind,” I say, and hang up.

We decide to go out for dinner so we will have less time sitting around in the dark. Every time the power has gone out it has been in the afternoon or evening, and now, with Daylight Savings Time, we have longer and longer to wait until the crews fix the lines, always the next morning and sometimes not until late the next day. As we drive to the Lebanese restaurant on Frenchmen Street, we pass by the Washington National Guard’s post at the creative arts high school a few blocks from us, by the river. This is the high school of the Marsalis kids, of Harry Connick, Jr., of Kermit Ruffins. It is now the only place in the neighborhood with electricity. Spotlights powered by generators make the place glow like a state fair. A guardsman and woman sit on folding chairs at the entrance and nod congenially to us as we pass. They will be leaving at the end of the week, I tell Simon. We are both quiet. We, who are liberals and never thought we would see the day when there was a military presence in our own hometown, have been changed by their presence. We have never felt this safe before. We don’t want them to leave. “Who will we go to if we need help?” I ask.

“The police,” says Simon. He sounds almost sarcastic, but I know that I am projecting. The Brit in Simon expects things to work as they are meant to, and the Southerner in me finds that notion almost comical. The one time I called the New Orleans police to come to my house because of a suspected break-in, they almost laughed at me. They suggested that I move.

“Ha, ha,” I say. Even the Louisiana National Guard has a bad reputation. The bartenders at Mimi’s say that they are the ones who hassle them about the curfew. They have ideas about New Orleanians. They don’t find us charming. I tell Simon that we should write a thank you card, maybe buy them a few cases of Abita before they leave, and I work on my letter in my head—how I will tell them about the first night back, when three young guardsmen helped me find my lost margarita I’d set down on the sidewalk. How I will remember to them the moments they shared with us on Halloween weekend at the corner of Royal and Franklin.

That night, a transformer on the telephone pole standing directly over the crowd blew, eliciting a few shrieks from the crowd, and then later, delight. The bartenders at Mimi’s lit seven-day candles and the Washington National Guard turned left their Humvee lights on. The New Orleans police showed up and it was clear that they wanted us to disperse, to go home, but they stood around, impotent. I’d like to think that they envied the Guard then, how the Guard really was only there to protect and serve us, not to prevent us from having a good time. In my letter I will tell them how I will miss feeling as if a figure of authority actually respected our rights.

At Mona’s, we order our favorites—chicken shawarma for Simon and a gyro plate for me. We talk about our wedding, which we have yet to set a date for and which seems an impossibly long way off. We want to have it in New Orleans but have already agreed that our initial plans to wed in January were far too ambitious. It’s not that we couldn’t plan it by then, it’s just that we don’t want our family and friends to see our city this way. I imagine my relatives pitying us, wondering what the hell we are thinking, living in a place like this. On occasion—and often when the lights are out—we wonder the same thing.

After dinner we run into James Singleton on Frenchmen Street. He’d played a few nights before at d.b.a. and we danced and danced and I nearly cried, I was so happy. I ask James if the rumors are true: has he really relocated to Los Angeles. He says that yes, he has, but that he is not abandoning New Orleans. I whine a little and give him the hard time I’ve given everyone I know who’s decided not to return. We need you, I say. How can the city recover without you, I say. But I can’t blame James. For all of its musical glory, New Orleans has treated its musicians horribly. Most of the nola musicians I’ve known have either had to take on second jobs simply to scrape by, or have gigged six days a week. How can you ask the musicians to return to this when they are being lured by other cities—cities where people are living, working, and have money to support our musicians who are, by now, both an object of pity and a spectacular “steal.” I can’t help feeling like New York and Austin and Portland and L.A. are stealing our culture from us. It frightens me. The idea of James Singleton sitting in a traffic jam on some L.A. interstate frightens me.

But: “I’ll always come back to New Orleans,” he says. “I need New Orleans,” he says. He gives me one of his spritely smiles and declares, “New Orleans feeds my soul,” and I know exactly what he means.

Monday, September 26, 2005

September 6, 2005

Volunteering as Red Cross Case Worker:

Dawanda and son of Uptown New Orleans: $910

Anna Polk and husband of St. Bernard, who were rescued from their roof and who smelled of mold: $910

Dawn Carter, husband, and son of Gentilly Forest: $1280

Dawin of Kenner: $665

Elaine Sheldon, trainer: teary and strong, like a tough and tender mother.

What an exhausting day. I will recount it later.

September 7, 2005

Fox:

“Memo Shows FEMA Chief Delayed Asking for Help With Katrina”

Red Cross said on The O’ Reilly Factor last night that they were not allowed inside the city because of a “local decision.”

Forced evacuations now expected to be carried out… beginning sometime today. A question, though, is how many people will come under this category.

“More pumps are arriving day by day from various places across this country and also from countries like Germany and Holland.”

“Are people going to be forced to go to other states or forced to live on a cruise-ship? People are anxious to get settled.” --Houston. “People say that they are getting the runaround, that no one is talking to them.”

“You can’t do that! They need to let us really know what is going on. We can’t be running around like chickens without heads.”

“Dome-City” has its own zip code.

Katrina will probably wind up costing the economy about 400,000 jobs. Could pick up as an unprecedented rebuilding begins, estimated at 200 billion dollars. Much of this depends on how hard Katrina hit the energy infrastructure. All of this as Wall Street watches the weather—Tropical Storm Ophelia off of Florida.

September 14, 2005

Not surprising, given my track record, that I am not writing again until now. So much has happened, of course, so much that I will forget. Me and my lack of discipline.

Most memorable, actually, has been the good time we had with Bill and AC and Sally and Chuck. Sally had us over for dinner and AC and I talked about my Bread Loaf experience and we worried together about the future of New Orleans. We smoked too many cigarettes, drank too much wine, stayed out too late dancing at the Northpoint Tavern, where a blues band called The Vipers was playing. The band was really good, but folks here don’t know how to act! Girls flipped their hair and yelled over the music to each other. Men cast their eyes about, looking, looking for ladies. Only two people danced, and they were, appropriately enough, blitzed. The star of the show was one dancing lady who might as well have had a pole. I did my pseudo backup-dancer dance, and thought about trying to sing with the band. A Michael Ray look-alike played his trumpet, and maybe it was wishful thinking on my part, but he even sounded like Michael Ray. It was not home, but it felt closer to it than anything so far here in Atlanta. It was so, so, good.

What I’m most worried about now is that we are losing our musicians. Really, imagine you are a New Orleans musician, always struggling to get by. You’ve evacuated, or you were trapped, in either case, you left your instruments behind. Gigs got cancelled. Your band is scattered across the country in the spare bedrooms or friends or basements of parents. You consider the future: you could return to New Orleans, though which bars would remain open, you don’t know, and those that do—will they pay? Will you be made a fucking martyr, asked to play as if you are again a street musician? And anyway, who else will return? Your bass player has decided to make a go of New York. Your guitar player has decided to relocate because he has kids and the future of raising kids in New Orleans—already an iffy prospect—is now even more bleak.

Or: you could move on like the bas player, the guitar player. You could ride the wave of the new New Orleans Diaspora, traveling to cities where you are now a novelty, and where people are as eager to fill your tip jar as your relatives and friends have been to push money-filled envelopes your way. You would be a big fish in an even bigger pond, but for the first time, perhaps ever, people would really fucking dig your music. You could spread the love! You could share New Orleans with the people of San Diego or Portland or Little Rock or Albuquerque. You could play your part elsewhere, and one day, one day, maybe return for a reunion of sorts. What would you do?

Other musicians who will be missed: the marching bands. Arthur Hardy is swearing that Mardi Gras will roll this year, and I think he’s right, but with what bands? And where will the children be? The high school marching bands? What about St. Augustine, with their golden helmets? Is their bandroom under water? Will they return?

September 14, 2005

Working as a case worker wit the Red Cross, the most noteworthy thing is the number of people I talked to who DO NOT plan to return. Not only were the poor the ones who were left behind, but they are also the ones who seem to be leaving New Orleans. I know that to some people this must seem like a great gift. The crime—vanished! But the culture will vanish, too. And I know, I know, that another one will emerge, but I envision a bunch of the Bywater-type weirdoes on their vintage bicycles, riding in Mardi Gras parades whilst beating—unmusically—on the lids of pots and pans. It is culture, but it is not the culture that was born of poverty.

I do not mean to suggest that we should want the poor in New Orleans to return simply so we can latch onto their second-lines, their jazz funerals, their neutral-ground Barbeques. I think, in fact, that what we have on our hands here is an enormous opportunity to alleviate poverty. It’s just: say you have very little, and then Katrina takes what little you have from you. Say you were at the Superdome, or the Convention Center. Say you witnessed the dog-eat-dog shit that went down in New Orleans in the days immediately following Katrina. Say you went without water, without food. Say you saw Geraldo Rivera reporting, and STILL saw now help? Say you were separated from your pets and sent to a shelter? And say that then you started to think about it: what will you do now? What is there to go back to? You know that your house is gone. You didn’t own it. You know that white folks will be swooping in with their ambitions to rebuild. You know they will want the most for their money. You know that now the upper-class folks across the country—the same ones, perhaps, who are helping you out now—will be the first to want to go into that rebuilt city, to renovate the life out of it. You know from experience that you are NOT given a fuck about back there, that you were not given a fuck about in New Orleans. Why go back?

Now, lest you think I am Barbara Bush here (Barbara who made some comment about the situation of the people in the Houston Astrodome being somehow BETTER for them,) let me just say that I don’t think this post-Katrina outpouring of generosity makes shit any better, at all. If you’ve lost everything, you’ve lost everything, and a fucking prize is not going to change the nature of that loss.

It’s just, I think it is crucial that we hear from the people hardest hit by Katrina. They absolutely should have a say in the way their city is rebuilt. And how will we hear from them? These people who no one has listened to, why should they expect to be heard now? I want to find them, to compile their stories, to hear their hopes for a new New Orleans—whether or not it is one they plan to return to—because they need to have a say in its rebuilding.

Mayor Ray Nagin has said that he will make SURE that the people who the storm replaced will be the ones to rebuild it—but how? And he, a former Republican, a former Cox Cable executive—how can we rely upon him to look out for our city? After all, it was he who was responsible for us in the first place, and look what happened.

Am I just an idealist, or is it supremely fucked-up that Halliburton was among the first to get a contract in New Orleans?

I am worried, too, about the fact that Congress has repealed he Davis-something-or-other act that requires employees to be paid properly in jobs of construction, etc. The Repugnants are saying that this is a great idea because it rids the process of all the red tape that might keep progress from moving quickly forward, but we know how willing they are to sacrifice the people for progress.

I just am so SCARED about what happens next! This whole event has made me feel so powerless, and I feel even WORSE knowing that the people who made New Orleans so wonderful to live in might be the exact same people who is leaves in its proverbial dust.

Other excitement that occurred between last week and this:

Whilst having margaritas at Los Loros (my favorite restaurant to go for some festive respite,) we met a woman name Kristine who works for CNN. She, like everyone who learns we are form New Orleans, wanted to do something for us, so she gave us her card and suggested that the camera crew might film pictures of our house that we could see… We ended up getting a call from the producers of the Anderson Cooper show, instead. They were hyped on filing us returning to New Orleans, and we had hopes that they would help us get in (you can’t get in without a press pass or rescuer credentials, etc.,) and then just as we got excited, they moved on to another idea. Oh—we were meant to be on tonight! I must go see what he’s got, instead.

It’s hard to hear these stories of heroism. I wanted to be there to help! I want to be a hero of this storm. Instead, I am a reluctant—and very lucky—victim. I want to have rescued people, to have rescued pets. And yesterday, on the nola.com pet forum, I noticed that someone said, “Where are the people of this city? Why are we taking care of their animals? Why aren’t they coming to help?” Is this a good question? Should we be there? Or should we be waiting, as we’ve been told. I don’t know, but I don know that I feel fucking helpless.

Blanco is making a lot of promises. “We’re not simply going to rebuild the same infrastructure.” We’re not simply going to rebuild the homes and the schools, she says. Instead, she invites all New Orleanians and the nation to join in an effort to create one of the best public school systems EVER!!! (Polite applause.)

See: even when it is a wonderful things—even when it will be “ a better New Orleans”—it will never be the same. I said to Simon yesterday that I have not felt like going back in time very often, but now I want to, soooo badly.

“Dear God, please bless the citizens of Louisiana, and bring all of our sons and daughters home.”

All I know, is that city had BETTER BE 75% DEOMCRAT LIKE IT WAS BEFORE THIS FUCKING STORM!

September 15, 2005

After watching Mayor Ray Nagin on “Larry King Live” last night talking about getting the city back up and running soon—perhaps sooner than anyone expected (“We’re gonna shock some people,” he said,) Simon and I decided to go to the Red Cross Headquarters for verification of our training so we can get into the city. Uptown, the CBD, and the French Quarter will be allowed back in as early as next week, and I heard from one of the clients at the Lithonia Megacenter today that the Convention Center will be used as a grocery store and lumber yard. I saw on Nola.com that there is now sewer service in the Marigny and Bywater, so we are eager to get back before there is a big traffic jam or rush. We know that I will be uncomfortable—and actually we think we’ll be staying in Baton Rouge with Brandi’s parents—but we just want to be back so badly!!!

The Lithonia Megacenter was indeed “mega.” The building is just off of Panola Industrial Boulevard, in the either defunct or temporary empty headquarters of Lithonia Lighting, 20 miles east of the city of Atlanta. We weren’t prepared, in fact, for its mega-ness, especially after the Monroe Headquarters had been cleared out. Somehow it seemed like the demand had simply tapered off, but that is far from the case.

In fact, when we were at Headquarters today, Kathy of the volunteer orientation room warned us to expect frayed nerves. They’d already called the cops today, she said. People just didn’t seem to understand—or be willing to deal with—the fact that their checks wouldn’t be available for another day.

The parking lot was full, and there we were, one Louisiana license plate among many. The parking lot looked like it had been the sit of a parade—an Icehouse bottle in one space, a diaper in another. Port-a-potties were set up next to the entrance, and groups of girls were flirting with guys, smoking cigarettes, a bit of normalcy.

The interior of Lithonia Lighting is as big as my entire high school. Exposed steel beams line the ceiling, and giant fluorescent light fixtures add to the industrial-feel. Police barricades and yellow caution tape marked off areas for computers, for discount clothing racks, for the cafeteria tables arranged set up for the various services available (school registration, housing vouchers, food stamps, health care referrals, MARTA assistance, a bank line for Red Cross vouchers,) for the many waiting areas filled with folding chairs intended to make long lines more comfortable. And, in fact, the lines were organized, too—one took a yellow ticket with a number which was then called out on a PA system, that screeched occasionally, annoying, but mere background noise at this point. The building buzzed.

We went to work. Again the system had changed. The manila 901 folders were a thing of the past, just like the debit cards had disappeared a week ago. A week ago we checked Ids much less fervently, erring on the side of sympathy when clients said they’d lost everything.. Now, ID was check thoroughly. (Last week, we found out that a single family had been awarded over $5,000—much of which was returned, but… and then there was the story of Ms. Hogg, and Atlanta resident who posed as an evacuee, and, along with her eight-year old son, even moved in with a 22-year old Georgia State graduate, who ended up calling the cops.) The system was now both more and less thorough. No longer to we record narratives. No longer do we ask if clients need medical assistance. We simply check and double-check Ids and issue checks.

But for me, it is different, and today was a wonderful day of connecting. The Red Cross Headquarters first of all discovered that we are from New Orleans, and their PR department came downstairs, eager to use our story for their image. Then, they sent us on to do casework, rather than the humdrum filing and copying that now takes place at Monroe. And in the casework, I met Sidney and Wendell-both men in their sixties who looked far older than that, and both men from New Orleans who wanted to return. Wendall of Soniat Street even teared up when I asked him his plans. “I’ll go home,” he said. “I’ll go home.” I told him how happy it made me feel to hear that he planned to return, and nearly cried, myself.

Later I saw a former student of mine—a young black real estate agent who nearly failed my class, but who I pulled through, with great additional effort on my behalf. He plans to return, too, and I can see how the upper-class in him has affected his perspective on the rebuilding of New Orleans. “It will never be the same New Orleans,” he told me. “It will be better.” He talked about the ninth ward, about how the laws of imminent domain will displace people, unfortunately, but that may not be an altogether bad thing.

I am torn on this issue. There was an editorial in the AJC today about the danger of gentrification in the rebuilding of New Orleans, and here I am—a genrificationee—worrying about what more white people like me will do to our beloved culture. Oh… I just am so WORRIED about the city’s future.

After we did casework, I walked past a young woman, her arms covered in cursive tattoos of boyfriends past, and she asked me if I could give her gas money and a ride. She and her son were sitting on an island of her luggage—a massive amount of it, her whole life packed away. So Simon and I cleared out the cab of the truck, and Andrea, her brother AJ, and her son Vondrice rode with us to downtown Atlanta. They’d been in Baton Rouge with family and had made the difficult decision to relocate—to start over. Vondrice said hardly a word. He sucked on a grape lollipop while we talked about Andrea’s and AJ’s home in Plaquemines Parish. They’d lived in a trailer given to Andrea by her father, and the trailer was now flooded, gone. AJ wanted to return—sooner to check on the damage, and later to be a fisherman again. I think AJ must be no more than 24, Andrea, 26. Vondrice is six, and what he said when I asked him, “So what do you think of all this?” indicated both the resilience and vulnerability of a child: “It’s nothing.” He kept talking about “diving right in” and a swimming pool and an aquarium. “Where’d the swimming pool,?” I asked him. “The aquarium? In New Orleans? In Baton Rouge?” Vondrice said: “In my backyard.” “Aw, that’s nothing,” I said. I won him over.

To be a child living through this! To say that it’s nothing, when of course it must feel like everything!

We dropped them off at the Days Inn on Spring Street and Andrea tried to give me a twenty. We both got teary when I told her she must be crazy, trying to give me money. “We went through this, too,” I said. We hugged. We hugged again. I gave her my number, and while they checked in, Vondrice and I tried to stare each other down. The excitement was now apparent—a swimming pool in a hotel! Two weeks, the Red Cross will pay for, and then… and then? I worry about them. Maybe they will call.

WARNING: I took notes during Bush’s speech, many of which need editing (as most of this blog does…)

Bush gives his “Presidential Address on Hurricane Katrina Recovery” from in front of the St. Louis Cathedral. September 15th, 2005. (I don’t know why I bothered with my crappy effort at typing this--

In Chalmette, when a man tried to break into a home, he was invited in to stay. (Aw, yes, even amongst the poor, there’s sweetness. If only all poor people were like that!)”A powerful American determination to clear the ruins, and build better than before.” “Our whole nation cares about you” (no, hey don’t.) This pledge:

“Throughout the area hit buy the hurricane, we will do what it takes. We will stay as long as it takes…” (Don’t use your language of Iraq on us!) “There is no way to imagine America without New Orleans, and New Orleans will rise again.”

Objectives:

1. To meet the immediate needs of those who left their home and all of their possessions behind. Dept of HS registering evacuees. More than 500,000 have gotten emergency help. “That’s 1-877-569-3317.” “we will pay fro your travel to get back to your loved ones” (except Andrea said she had to pay $100/each for them to get to Atlanta to a new life. I have asked for more than 60 bullion.

2. To help citizens pf Gulf Coast overcome this. Get people out of the shelters by the middle of October. I will work with Congress to ensure that the states are reimbursed. Housing is urgently needed for rescue workers and the workers who will rebuild the area. The temporary housing will be as close to the construction area as possible to they can rebuild in a “sensible, well-planned way.” “Our goal is to get the work done quickly.” “There will be many important decisions an many details to resolve.

The federal government will be fully engaged in the mission, but local government will be in control of the planning and rebuilding…

3.) When communities are rebuilt, they must be even better and stronger than before the storm. “There is also some, deep, persistent poverty that has roost in racial discrimination…” “More families should own, not rent those houses.” “Americans want he Gulf Coast not just to cope, but to overcome.”

“We’ll build HIGHER and better” (Make the pie higher!)

I Propose:

The Gulf Opportunity Zone. Immediate incentive for businesses. It is entrepreneurship that helps break the cycle of poverty.”

Worker Recovery Accounts of up to $5,000 for job training, education, and child care.

Urban Homesteading Act: Provide building sites to low income people free of charge, based on a lottery. They in turn will agree to build… (Habitat.)

“Protecting a city that sits lower than the water around it is not easy…” City and state will have a large part in the work that ensues (levees.)

“The Armies of Compassion” give our reconstruction effort “its humanity.”

USA FreedomCorps.gov—an information clearinghouse so that families can find work within the regions.

“In this great national enterprise, important work can be doe by everybody.”

“The danger to our citizens reaches much farther than a fault line or a floodplain.”

Immediate review of emergency plans in every major city.

Massive flood, major supply and security, and an evacuation of more than 1,000,000 people.

“The systems was not well-coordinated… it requires greater federal authority… When the federal government fails… I am responsible for the problem, and its solution.”

“Better prepared for any challenge of nature or act of evil men…”

“Every time, the people from this land have come back to build anew. Americans have never left our destiny to the whims of nature…”

“Yet we will live to see the Second Line.”

THAT WAS A FUCKING GREAT SPEECH!!!! Wow…

Tim Russert’s comment: one speech alone will not solve his political problems. “It’s a tall order—he began tonight.” “New Orleans is an American city that has a real soul…” but many are afraid that we may not be able to capture that…

The first American City of the 21st century to be rebuilt… and we can take place in that.

September 17, 2005